The Small-Scale Rental Sector: An Understudied Population of Mostly Individual Owners

Before the modern ghetto collapsed in the postindustrial economy, real estate brokers developed a new technique of exploitation, one focused on selling black families houses “on contract,” often for double or triple their assessed value. “The reason for the decline of so many black neighborhoods into slums,” writes Satter (2009, p.5), “was not the absence of resources but rather the riches that could be drawn from the seemingly poor vein of aged and decrepit housing.” (Desmond and Wilmers, 2019)

The collapse of the housing bubble with the Great Recession, and the ensuing waves of foreclosures in the city of Minneapolis, hit distressed single-family housing markets on the north side the hardest in 2010. According to the City of Minneapolis Department of Community Planning and Economic Development (2015, p. 5) report Housing Investment Analysis: 2008–2014, “The Twin Cities was in the top 10 highest rated metropolitan areas for fraudulent mortgage activity in the country which contributed to the recession.” This economic tsunami was further exacerbated by the 2011 tornado in North Minneapolis, which created hundreds of vacant and boarded-up properties in an area where over 60% of residents were already receiving county assistance (Wheeler, 2012).

According to the report Uneven Recovery: A Look Back at Minnesota’s Housing Crisis, published by the Minnesota Housing Partnership and Minnesota 2020, North Minneapolis and nearby neighborhoods in the west metro have struggled the most to recover from the recession because of “enormous loss of home wealth, expensive and hard-to-find rental housing, and lagging incomes” (Egerstrom and Rosenberg, 2014). Across the metropolitan area, an economic transformation is taking place, whereas in many neighborhoods a distressed housing stock has been converted into mostly rental occupancy due to cheap acquisition costs for investors. This is especially true in high-foreclosure areas like North Minneapolis. Although this process of individual investors targeting low-wealth communities has been taking place for years, recently it has become widely recognized that a new institutional asset class of large real estate investment groups have entered the landscape and rapidly expedited the process of destabilization in North Minneapolis, as well as similarly situated inner-city urban communities all across the country.

Little research has been done on the small-scale rental sector made up of mostly single-family homes, which accounts for nearly one-third of the American rental housing stock (Mallach, 2014). In the Twin Cities, a great deal of organizing led by Inquilinxs Unidxs Por Justicia has surrounded the fraudulent mismanagement of large multifamily housing buildings in areas adjacent to downtown in South Minneapolis. However, it was not until former North Minneapolis landlord Mahmood Khan’s rental licenses were revoked in 2017 that a discussion about the city’s most distressed housing stock went from the margins to the center of public policy discussions. The majority of Khan’s 43 properties were duplexes and single-family homes. The exploitative nature of rental housing in North Minneapolis, and the fact that close to 300 families faced homelessness due to the revocation of Khan’s rental licenses, shined a light on an issue that the city of Minneapolis is still trying to navigate. The Minneapolis Star Tribune (2016) reported that between 2008 and 2015, Khan’s properties racked up more than 3,550 housing violations.

A more recent investigation by Fox 9 News (2018) on a Georgia-based company named HavenBrook Homes highlighted the ability of large investors to buy single-family homes as investment properties in areas such as North Minneapolis, prohibiting local residents from purchasing their own homes. HavenBrook Homes purchased 400 homes in the Twin Cities, half of which are located in North Minneapolis. This investment strategy only reaffirms that the community has been and continues to be a place from which to extract wealth, thereby continuing the life cycle created by history of redlining, racial covenants, disinvestment, predatory lending, gentrification, and displacement.

There is a fear premium attached to North Minneapolis. Because what's the stereotypical image people have of North Minneapolis? I could tell you. Bang, bang. People are afraid of it. If you tell people, I bought a property in North Minneapolis, what they say is, "Why would you do that?" I say, "Because it's like pretty much anywhere else." You got about 90% of the people who are fine. Then you got 5% of people who are sketchy. You got about 5% who are actually all your trouble people. That pretty much carries through anywhere. We had a drug house on our block. You don't think it's going to happen in suburbia on a cul de sac. It happens. That fear premium is that values there would be pressed, not only by the mortgage crisis, but by the fact that people don't want to own property there if they're afraid. (White male, 58 years old, property manager and owner)

The Illusion of Choice report moves beyond the limiting confines of quantitative analysis to the understudied realities of mostly small-scale individual landlords to understand from their perspective how and why close to 50% of renter households in North Minneapolis experienced at least one eviction filing (Minneapolis Innovation Team, 2016). The in-depth interviews that CURA’s research team conducted with 32 landlords helped to determine:

- what policies and procedures landlords have in place to determine that eviction is the best course of action for dealing with a tenant;

- how landlords determine the cost-benefit analysis of evicting a tenant and more generally owning rental property;

- what practices landlords employ once the decision to evict is made, including whether and why those practices are employed for certain rental populations.

These findings aim to help better inform how the city and state can work with landlords as partners in community building.

Landlord Profile

This report’s landlord findings are arranged to examine three major themes:

- motivations for becoming a landlord,

- assessing risk and mitigating loss, and

- the role of nonprofits or government-supported housing agencies. (Note that landlord names have been changed to protect the anonymity of the interviewee.)

The three themes are examined in separate sections, each beginning with a short case study and followed by the emerging concepts as evidenced by actual statements made by landlords in their interviews. Finally, we end with a summation of how the themes examined in context relate back to how and why eviction trends are taking place in North Minneapolis from the perspective of landlords.

Motivations: Small-Scale Landlords in North Minneapolis

Jack is a White male landlord who has owned and managed properties in the Twin Cities since 1977. He currently owns 30 properties in North Minneapolis. Jack was in real estate, naturally gravitated into real estate investment, and became a landlord who pursued North Minneapolis because the acquisition costs were cheap. In a tight rental market, Jack is more selective, but at other times he would take anyone who could “fog a mirror” to fill a vacancy. “I think, if you have very regimented requirements, and very strict guidelines, I think you'd be better once you get the tenant. However, that comes with a price. If you're gonna really hope people will come, and only take the top-notch applicant, you're gonna have vacancies, 'cause you're not gonna fill places." Jack admits that in the beginning of his career, he was kind of sloppy in his screening process, but it has become more formal through the years.

Jack has a new property manager, Deana, whose philosophy he does not 100% support, as she is willing to work with people with a challenging past and make nontraditional arrangements. Deana, whom Jack calls a “Den Mother,” is a property manager with a self-described broken past. She has a criminal background but has been out of the life of “drugs and prostitution” for 15 years. Deana is called to the homeless, because she can identify with their needs. She is most interested in working with those people living in Jack's properties with a difficult background, which is somewhat different from how Jack has managed historically. Deana is interested in helping to give people a second chance.

Jack is adamantly against someone with violent felonies. If a tenant has a prior unlawful detainer, Jack talks with the former landlord to ensure all debts are settled. He will also collect a larger deposit, as he sees those applicants as major risks to his investment. Unlike Jack, Deana will arrange unique weekly payment plans instead of once-a-month payments with tenants. She believes that most people who have experienced housing instability in the North Minneapolis area must be taught how to manage their money when their incomes are often inconsistent.

To test her approach, Jack recently gave Deana a property with three people who she determined did not have enough money to move in. Deana stated that it took a month to iron out the “bumps” of her working relationship with these tenants and clarify what they needed to do. Unlike some landlords in North Minneapolis, Deana tells people up front that there is an application fee and will only collect the fee if they are getting into the property. She asks people to be honest about their backgrounds, so that they (Jack and Deana) can decide whether or not they can work with them.

Jack has given Deana about 10% to 15% of his properties to see how it goes with her approach, although he is skeptical. He does not believe it is sustainable but is willing to allow her to try it out. Jack reiterates that Deana is then responsible for the tenants she takes in. “I keep telling her, she's looking at life through rose colored glasses, and I keep saying to her, I hope these people work out.”

Deana recalls when she went to collect the rent from one of Jack's tenants and learned that the tenant had relapsed 2 to 4 months ago. The tenant later came up with some of the money, but he needed help. Deana does not agree with Jack that if a tenant pays a deposit (or double deposit for those with troubled backgrounds) and first month’s rent out of their pocket, that they are usually better tenants. She argues these folks are borrowing to pay those deposits and that's what the county is for, to help those people. Both Jack and Deana value the county emergency assistance program but believe that the process must be quicker. "In the old days, it used to be quick. If somebody went to emergency assistance, and you get a call in a few days, and then the check would be next week. Okay. Now sometimes it's 30 or 30+ days and that puts a hardship on the landlord, because now he's not getting his money, and you've got other payments to make, and other bills to pay, and you've got to wait.” Deana is currently trying to convince Jack to begin to rent rooms instead of entire homes or units to one family, as she believes that will be more financially sustainable for the people she is trying to serve.

Jack’s 40+ years of experience has led him to resent the city for making tenants’ issues the landlords’ responsibility, such as inoperable vehicles or unlicensed tabs on the property. He feels the courts cheat landlords and does not agree with arguments presented by Legal Aid that compare the homeowner foreclosure process to the tenant eviction process. Jack does not see the city police as an ally, particularly the forced use of the crime-free addendum, which made the tenant responsible for all drug- and crime-related activity. Jack was forced to evict someone due to an arrest without a conviction. He later appeared on the popular TV show Hot Benchwith his former tenant, a tenant he had preferred to keep. The California judge stated on live television that the crime-free addendum was unconstitutional, as the tenant had not been charged with a crime.

Although Deana supports unlawful detainer expungements, Jack does not. He noted:

“Very seldom do I feel that a tenant deserves, or should have his or her record expunged, because my experience is, when someone's been evicted, they've had plenty of opportunities not to have it on their record. And I feel like they have got this form there, the comments are ‘may the public be benefited by this being removed from their record?’ And I feel, as a landlord, I don't want a tenant to come in and apply for a property, and they just had their record expunged, and it's not there. I wanna know what's on their record.”

Deana described attending an expungement hearing: “She [the tenant seeking expungement] needed to get her record cleared up, so she can move on with her life. You know what I mean?...Expungement is another opportunity for people in the 1-1 [55411] and the 1-2 [55412 zip codes], particularly, to get a second chance at life."

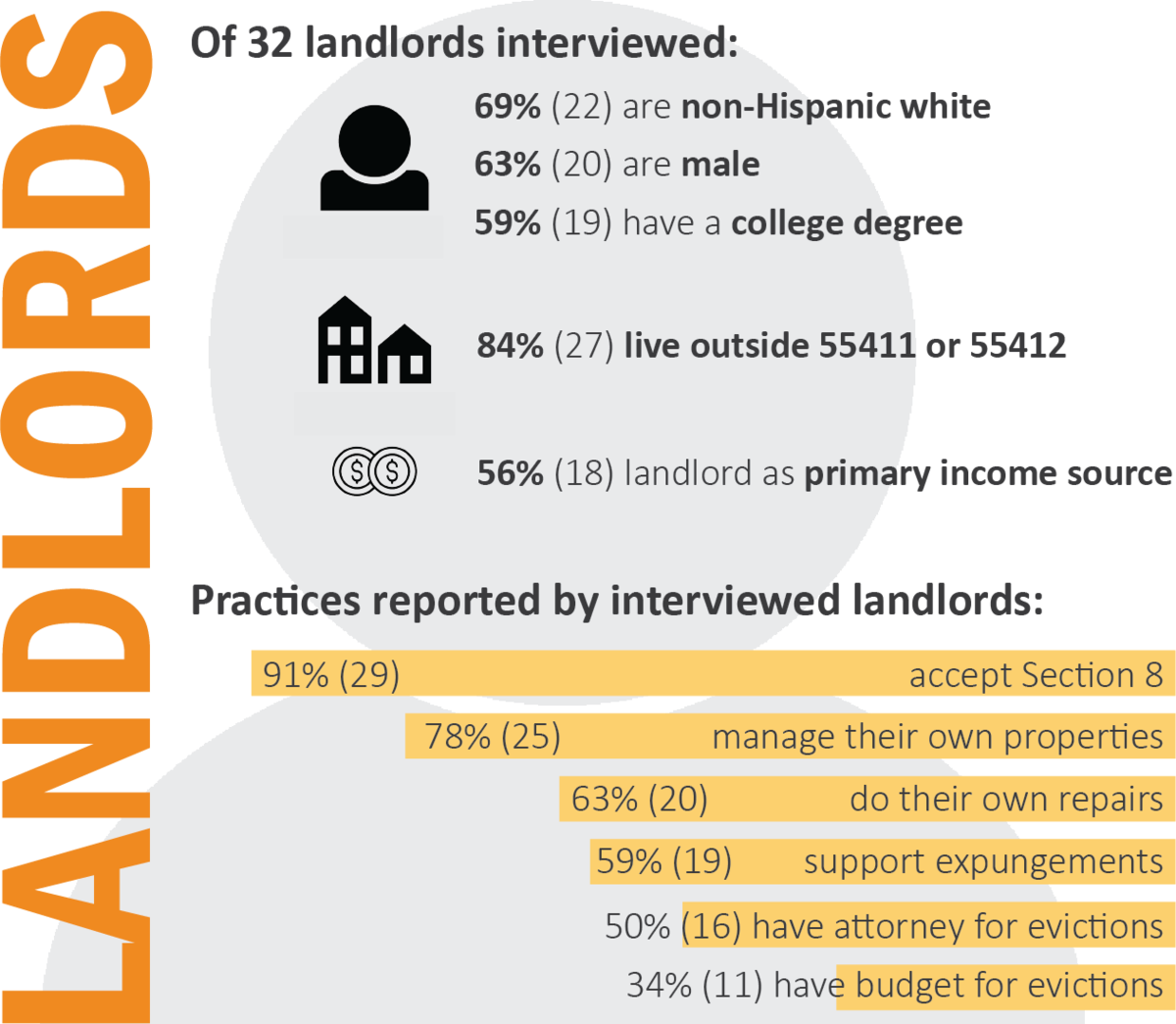

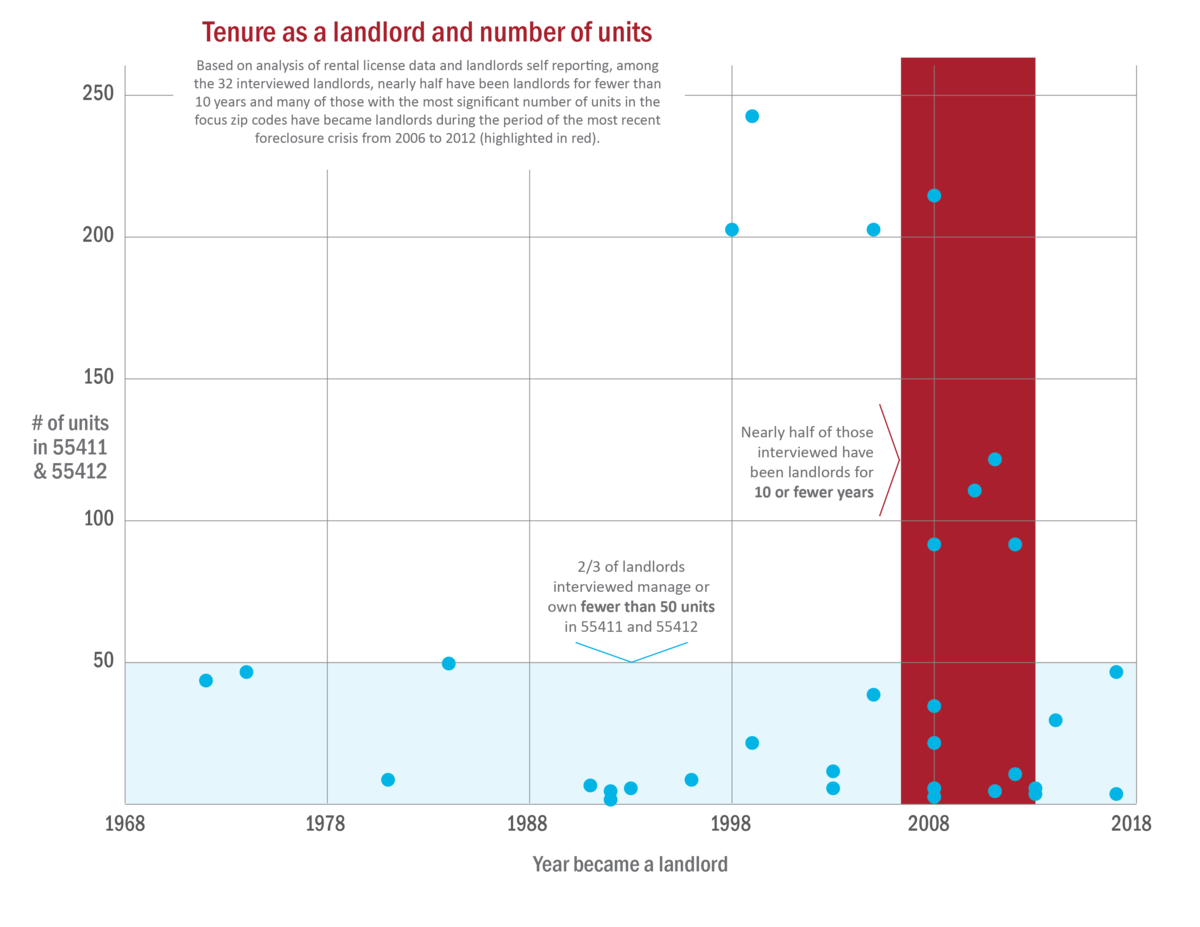

Jack and Deana are exemplary examples of the tensions that many landlords and property managers face. Over 90% of the private landlords interviewed aligned with the opinions Jack expressed, with few coming to the work of property management with the same ethics as Deana. Jack and Deana’s interview illustrates a host of challenges that all of the landlords we interviewed must confront to some degree, as they make decisions around their motivations to become landlords or property managers—which in turn directly impacts how they understand the use and purpose of evictions. In this case, Jack is a middle-aged White male, not from the community, who has had a long career in real estate and property investment. Similar to Jack, all of the landlords we interviewed stated that they purchased in North Minneapolis because acquisition costs were low, with about one-third of the property owners purchasing between 2007 and 2012, at the height of the housing crisis. Deana, on the other hand, one of only four of those we interviewed, became a property manager not to generate and build wealth but to earn a livable wage doing work that directly impacts the sustainability of low-income Black families in North Minneapolis.

Jack and Deana illustrate the spectrum on which landlords discussed their motivations for owning rental property or becoming a property manager in North Minneapolis. A common topic that landlords discussed is what influence the market and economic forces have had on both their perception of North Minneapolis and their decision to either purchase or manage in North Minneapolis. Landlords cited: (1) history of predatory practices, (2) the increased presence of large real estate investment groups, and (3) cheap acquisition costs. Predatory practices were cited by many landlords as a sign that North Minneapolis is always being manipulated by unscrupulous businessmen/women who aim to exploit a community that does not always have the right information or education to assess the nature of the products being sold. Yet many landlords noted the statistical realities of poverty and crime and used them as commonsense understandings to explain who the tenants were that they serve. A small minority cited the fear of large real estate investment groups that were seen as investors simply flooding the market when they sold. However, all of the landlords who we interviewed, most of whom were small-scale rental owners, stated that cheap acquisition costs was the primary reason that they purchased in North Minneapolis, or the owners who they managed for chose to invest in North Minneapolis.

Motivations for Becoming a Landlord

One hundred percent of the landlords interviewed identified cheap acquisition costs as one of the primary reasons they invested in North Minneapolis. Nearly half of those interviewed became landlords in the past 10 years, and one-third became landlords during the housing crisis, from 2007 to 2012.

I did the majority of my investing in that area around 2010 through 2012 and the main reason was because of how good prices were in the area. Yeah, and I took a lot of properties that were completely uninhabitable and renovated them and made them nice. I did full rehabs of the city to bring them up to modern day code. I put a lot of work into them...Probably [spent] between $30,000 and $50,000 and then it would usually require about that much in renovations. (White female, 35 years old, individual property owner and manager)

I looked at it and said okay, from a purely rational, financial standpoint, if I was to buy a property like if I bought a duplex in Burnsville where I could get...At that time, the first time I bought it was $885 a month both sides. If I was going to get that much rent in a duplex in Burnsville, it probably would've cost me about $180K. The duplex I bought in north Minneapolis was $89K. (White male, 58 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Mostly because it's a high rental opportunity, and we look throughout the entire Twin Cities. We work with some realtors and try to find houses that we can buy for cheap. I don't think we've paid more than $40,000 for a house. We can't get that kind of purchase price anywhere else. (White female, 36 years old, individual property manager and owner)

I chose it number one, for the price. The cash flow is really good. It is because unfortunately, it's not as desirable for the location. I think there's investors that won't even look up north, they wouldn't even consider it. (Black female, 44 years old, property manager for nonprofit agency)

During the real estate crash, I bought a couple of properties that were adjacent for a couple of reasons. Like that those properties affect me anyway and that they had crashed. They were maybe 15 cents on the dollar from before the crash. Not of real value but of inflated prices that had been paid before. (White male, 62 years old, individual property manager and owner)

But I like it. I'm waiting for the next crash [laughter], and I'm buying in North Minneapolis because I feel North Minneapolis is going to change. There's a lot of houses just burning down and then new developments pop up. So that's gonna increase the rent and that's gonna increase the value, it has to. I mean, downtown can't grow past the river. It can't move to Uptown. Uptown there's a lot of beautiful, beautiful houses in Lake Calhoun that they're not gonna tear down. So I think North Minneapolis is the easiest, cheapest way to go. I mean, I know that the district, the Section 8 office is, where the warehouse used to be, all that has changed a lot and it keeps changing. But I'm seeing a lot of change North Minneapolis, so I'm keep that in mind. I know it's changing. I know…Brooklyn Center really is getting screwed because everybody's moving that way. (Latino male, 34 years old, individual property manager and owner)

The most common reasons cited for becoming a property manager or landlord were that they “fell into the work” because of a lack of professional experience or for investment or retirement purposes. Nearly two-thirds of landlords owned fewer than 50 units.

When I got divorced, I moved into a building. The owner asked if I would do care taking for him, I said absolutely, this would be great for me. Several months after, the building sold to a developer, and I was hired on by that developer. What he would do was buy distressed properties, rehab them, we would re-rent them, if it was a cash cow, he would keep it. Otherwise he would sell it. It just kind of snowballed since then, 20 years later I'm still doing it. (White male, 44 years old, property manager for a for-profit organization)

I think, as most property managers, I kind of fell into it a little bit. When I was living in San Diego, it was an opportunity to have housing, and that was a part-time gig where I was getting a free apartment since housing is very expensive in San Diego. My wife and I were in a transition, so it was like, oh, I can do this a little bit. (White male, 32 years old, property manager for a for-profit organization)

I've been with [for-profit organization] for, I think it's about, 13 years now. And, I guess I got into it by chance. I did not intend to get here. I started out working with the maintenance side of the property management company. (White female, 39 years old, property manager for a for-profit organization)

Despite the acquisition costs of North Minneapolis, many landlords noted that according to popular perception, investing in North Minneapolis was quite undesirable.Across the landlord sample, a small group were seasoned investors—11 out of the 32 landlords (34%)—many of whom were licensed contractors, yet a majority of the landlords did not have long careers in property management or investment—21 out of 32 landlords (67%). When describing their tenant screening processes, several landlords openly admitted a devastating learning curve. Many stated that they were quite “sloppy” in their initial screening process, stating that when the market was tough they would take anyone, which would end up costing them time and money. Inexperienced landlords described that they initially failed to pay attention to things such as income and background checks.

Well I didn't do any, and then I got screwed doing that, and so I started doing background checks and then realized I'm just paying a bunch of money. Even though they were subsidizing the cost of the applications, I didn't really know what to do...Because the tenants weren't really up to the standards of who I'd want to rent to. So you just kind of go with your gut of whoever you think wants to turn a new leaf. (White male, 32 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Landlords stated that it was nearly impossible to find a tenant who did not have bad credit, to the point where they no longer used credit history as a determining factor for residency. This finding frames the ways in which landlords create a typology of what the typical North Minneapolis tenant is like, prior to taking an application or meeting them face to face.

Yeah, and I really don't go looking at credit because I know that many people who apply for properties in North Minneapolis, they don't have good credit. (South Asian female, 52 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Initially I didn't do background checks. And then I did a couple, I think I did five for one. And they all basically came back the same, bankruptcies, unlawful detainers, very poor credit scores, arrests, things of that nature. They were all pretty similar so I kind of do think why would I even do a background check if that's just pretty much the norm? (White male, 32 years old, individual property manager and owner)

The least common reasons cited for becoming a property manager or landlord were their careers in real estate led to rental property ownership or their entire careers involved the buying, selling, and rehabbing of properties typically with a construction or trades background.

I've been a landlord since 1984, since 34 years. It started out just owning one or two properties and gradually grew to, I got up to 39 properties. I'm down to 37 properties...I [also] have a tax practice. (White male, 60 years old, individual property manager and owner)

The reason I got into the business is that I worked construction in high school, so I knew how to build. It was all new construction of course, but being around the trades it interested me as far as doing plumbing and wiring, roofing, framing, all that type of thing, and so when I turned 22 I got my real estate license. (White male, 68 years old, individual property manager and owner)

I've been a landlord for 10 years, and I've probably been in property management for 35. I'm a licensed contractor...I had an opportunity to buy some properties, a couple of duplexes, 10 years ago, contract for deed, that were in desperate need of repair. And so I kind of got into it that way. Before that, I was a HUD [US Department of Housing and Urban Development] supervisor. I was in charge of 2,500 homes for inspecting. Also was in charge of the whole West Bank [University of Minnesota] as far as maintenance. (White male, 62 years old, individual property manager and owner)

These landlords typically stated that they were beginning to sell off their properties and aging out of the work. The era of the career landlord has certainly begun to decline, especially as many of those with a sizable rental portfolio, which they accumulated over the last 10 to 20 years, have begun to cash in on their investments and larger firms are buying more properties.

At the present time I'm at the end of my career pretty much. I'm slowly selling off properties. At one time I had over 100 individual properties, and I'm down to 57 at the current time. (White male, 68 years old, individual property manager and owner)

It's 37 [properties that I own], that'll probably be down to about 35 by the end of the year. I'm starting to sell and donate some properties. (White male, 60 years old, individual property manager and owner)

The Impact of Landlords’ Motivations on Eviction Filings in North Minneapolis

Alan Mallach (2014), in his article “Lessons From Las Vegas: Housing Markets, Neighborhoods, and Distressed Single-Family Property Investors,” uses a case study model to explore distressed property investor strategies in high-foreclosure areas across the country. In the case of Las Vegas, NV, real estate investment during the housing market bubble was dominated by “market-edge flippers” who bought properties in fair or good condition to sell back into the market for a modest profit when the market rebounded. Whereas in Detroit, MI, as Mallach explored, the realities of low purchasing prices with high property taxes invited the “milker” strategy. This strategy allowed for investors to rent out a single-family home, not pay property taxes, provide limited maintenance and repairs, recover the investment in 2 years, and then exceed their initial investment by more than 50% in the third year. The investor would then allow the property to go into tax forfeiture with no intention of owning it thereafter. In these two cases, the market drives investment behavior.

In the case of North Minneapolis, it is critical that we understand how the market also drives investor behavior. According to Mallach’s (2014) typology, North Minneapolis has seen three major types of distressed property investor strategies since the housing crisis. First, the “Flipper, predatory” model, where someone buys properties in poor condition and flips to buyers “as-is,” often using unethical practices for immediate appreciation. Second, the “Rehabber” buys properties in poor condition, rehabs, and sells the properties in good or better condition for immediate appreciation. Third, the “Holder, medium-long term,” where someone buys properties to rent out for an extended period of time for cash flow and potential resale in the near future.

2012, I got my first rental property. Why? Just, my strategy is to buy and hold. I tried the stock market, but it's too liquid for me. If I'm in trouble, I can always make a couple moves online and I'll have that money within a week. I mean, I try, I get a nice chunk of change and then something happens. It’s real estate. Real estate is not going to save you. It takes months to get the money out, and that's allowed me to keep growing my portfolio. I see it as my retirement. I mean, I probably…I’ve got a good portfolio. I'm planning on buying more. Right now that market is really, really hot. So I'm buying, fixing, I'm flipping. Buy them, fix them, sell them. Once the market goes down again I'll buy again, fix them, and rent them. (Latino male, 34 years old, individual property manager and owner)

One of them I got in 2015, the other I think in '14. I just got them because that was a time when the prices were really down, and I just got it because I don't have any plans of keeping them long-term. After maybe 1 or 2 more years, I'll just sell them. (South Asian female, 52 years old, individual property manager and owner)

I'm planning on buying more, like I said. I bought all my properties in the recession, the last house that I bought to hold was in 2015 and since then I've been just flipping them. Buying, fixing, because they're very expensive. They're very, very expensive. You need to buy free and clear to be able to make a dollar, otherwise there's not that much profit to be made. (Latino male, 34 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Most landlords discussed their investment in rental property using free market thinking, however, this does not control for social, economic, and political realities and the power imbalance between landlords and tenants. Simply, the landlord sets the rent and legally owns the property in question. To the contrary, free market ideology and rational choice theory suggest that all citizens can equally participate in the market, which ensures that everyone will be able to afford a place to live in the community that they desire to live in. However, that is simply not true. North Minneapolis has been, and continues to be, a place from which to extract wealth, continuing the life cycle created by a history of redlining, racial covenants, disinvestment, predatory lending, gentrification, and displacement.

Free market justification, particularly in a place like North Minneapolis, only works to reproduce predatory practices in a part of the city that has been manufactured to contain socially constructed, undesirable populations and extract its resources. A small minority of landlords divested from this model of thinking, one of whom called himself “altruistic” and proceeded to explain that his tenants suffer from a severe lack of income and become self-destructive and sometimes chemically dependent as a result. He worked diligently with them as they sought resources and support. “I understand how this is created, because as a country, we create these problems.” When landlords make decisions that are driven by the markets, the social impact for tenants becomes secondary, at best. This, in turn, provides zero incentive for landlords to avoid eviction filings. Rather, in many ways, a profit-driven motivation incentivizes eviction filings.

Assessing Risk and Mitigating Loss: Small-Scale Landlords in North Minneapolis

David is a full-time realtor and became a property owner/manager in 2013. He bought his first three duplexes from an acquaintance who was buying foreclosed properties in North Minneapolis after the 2008 housing market crash. This owner had been remodeling properties just to keep from laying off his crew. David bought one of these properties and described himself as a risk taker who saw a good investment. He explained that he was not afraid of the stereotypes that stopped other investors from buying in North Minneapolis. Contrarily, David saw a great investment and profit-making opportunity that he realized would not be possible in his own suburban community.

What shocked David the most about tenants is that when he sits down with them with the intention of reading through the lease, they just want to know “where to sign.” They don’t want to go through it. To David, this tells him that they don't feel like they have a say, because if they did they would negotiate.

David inherited six units with tenants when he purchased his first property. Two of his Section 8 tenants were grandmothers who could not afford the damage deposit, so he allowed them to pay a little additional money each month until they reached their full damage deposit amount. David emphasized his willingness to work with people as long as they communicate and don’t disappear. According to David, the most common challenge his tenants face is their social dynamics, which lead to financial hardships. “A girl gets pregnant, has a child, drops out of school, ‘baby daddy’ isn’t living there and is not helping, and she winds up living with her parents or on some sort of assistance. She can’t finish her education and things continue to snowball.” David further states:

I've only had two instances where a man has been on the lease with a woman. It's always women who are on the lease, and then if there's a baby daddy, he's the couch surfer. If I get police calls, it's pretty much always because of the guy. It's not the women who cause the problem. When it is the women who cause the problem, and here's another real area of interest to me, a lot of it has to do with mental health problems. There's a surprising number of issues there. It never would've dawned on me, until I got into it.

David goes further to say that entire households are raised this way, and he sometimes meets grandmothers who are younger than he is as a result of this cycle. “They're permanently in a bind, and to me, it's like a slow motion train wreck.”

He has only evicted one tenant. In this case, David was working with his tenant’s boyfriend to receive the rent. However, although the tenant was giving her rent money to the boyfriend, David was not receiving it. The boyfriend told David numerous stories about why they weren’t paying rent, including that his mom had passed away. Later, David learned from the previous owner that the boyfriend claimed that his mom died the year before. In reality his mom was still living. David met her a year later.

By the time David filed the eviction, the tenant and her boyfriend owed $3,000 to $4,000 in back rent. Since he had only corresponded with the boyfriend, David finally sent a letter to the tenant’s job to connect with her. She called David the next day and explained that she had no idea her boyfriend wasn’t paying. She took out a 401(k) loan to pay the back rent and handed David an envelope with $4,800 in cash.

Around the same time, the tenant’s boyfriend robbed a bank and as a result, the police raided David's property and found one-tenth of an ounce of marijuana.

The problem the police had with me, was not that he was a bank robber. The problem they had with me was that they found a tenth of an ounce of pot in the house. Pot is a schedule 1 federal drug. I learned a lot in this experience. It's classified as a narcotic. I got a letter from Minneapolis police saying, “This is a problem property, and you're at fault.”

David refused to evict the tenant, and when he later received a call from Luther Krueger (a former crime prevention analyst in Minneapolis), Krueger tried to convince him otherwise. In the end, David was forced to file a management plan by the city, because he refused to evict his tenant. He believed the boyfriend was taking advantage of his tenant and that she had no clue what was going on.

Through her 401(k) loan, David’s tenant got caught up.

Then she's good, good, good. Then she's not good. Then things fall off, she stops talking to me. All she had to do was tell me what was going on. The state was garnishing her pay because of some past due tax issue. Even though they weren't married, they were tied together. She wound up having money garnished. This is one of those, I've told her literally 100 times, you just have to talk to me. She still gets scared, and she stopped talking to me. Then I had the eviction action filed, because I hadn't heard from her in months. Got to the point where I was driving by, trying to figure out is she even there.

The tenant did not show up for any of the court dates and only called when the sheriff posted a vacate notice. David asked her if she was going to pay and stay or not. They agreed that she would stay.

David now picks his tenant up each week and collects as much as she can pay until her debt is paid. “Right now she owes me, I think she's $2,800 behind, but she's making progress. Is that smart or is that stupid? I don't know yet. Come ask me in 6 months.” David admits, he likes her and he believes in her. “She could potentially get further and further behind, and maybe I'll lose $5,000 or $6,000, and then I'm going to feel like, ‘Wow, I was the biggest sucker out there.’” He added:

I don't think it's going to happen. I think what I see is, she is going to make good. It's going to take a long time. I don't really care about that. I just want to know that she's going to make good. She has two kids, I like the kids. I like her, I just want her to understand, you got to talk to me through thick and thin. You got to talk.

The management plan enforced by the city aimed to ensure that similar problems with future tenants would not happen again. Now all of David’s potential tenants must apply through Rental History Reports, a third-party site vetted by the city, and David is “completely detached from it.” No one has yet to apply with any unlawful detainers, but he probably would not rent to them. To protect himself (unless the person is on Section 8), he will only sign a month to month to ensure they will pay consistently before signing a lengthy lease.

David made it clear that he employs these strategies because he is“not going to be Mary Jo Copeland. I'm not going to house people for free, because then I am costing myself. That might be selfish, but I bought these as an investment. An investment has to perform. You can still do it with heart. You got to balance off. Right and wrong, good and bad.”

For larger multiplexes, a property management company can typically maintain its cash flow even when a few units go vacant as a result of eviction. However, it’s more common for landlords who manage single-family homes, duplexes, or small multiplexes to have a more fluid set of policies or practices when it comes to the tenant eviction process. In addition, these landlords typically take on a higher risk of not being able to maintain consistent cash flow between periods of tenant turnover.

David is middle-aged white male landlord who stated that he had a fairly racially homogenous upbringing while growing up in Bloomington. Yet, he is a representative landlord who invested in North Minneapolis because he knew he could not make the profit margins elsewhere. He quickly entered a cultural context where he could not understand why his mostly low-income Black tenants did not try to negotiate their leases, and he was enamored by the fact that the grandmothers appeared to be younger than he was. David used phrases such as “culture of poverty” and “baby daddy,” which have become popular linguistic tools used to justify why we should blame low-income people for their circumstances rather than understanding the exploitative context under which these social dynamics were created. David used his new insights to determine that his tenants’ social dynamics led to financial hardships. When it mattered the most to him, he was able to support a tenant who many other landlords would certainly have evicted. However, he admittedly struggled with his own business interests and the needs of the people he claimed to want to serve.

Perception of Tenants: A Frame for Assessing Risk

Landlords typically described their tenants using deficit-based language that often included references to high rates of unemployment, domestic violence and intimate partner violence, driving while Black, getting pregnant at a young age, grandmothers raising grandchildren, no boyfriends on the leases, the majority of tenants being single mothers, and drugs. These perceptions ensure that any transactional breakdown in the relationship is understood to emanate from these presumed deficits.

I definitely think that there's enough money being thrown at this problem. I just think that it's being used poorly because we have major government-funded programs and then nonprofits surrounding that, plus a lot of other types of aid for furniture, food, cash assistance, medical benefits. There's plenty of ways for people to get the assistance that they need. I think that people need to appreciate it and they need to actually have...It needs to be structured in a way where it's not so easy for them that they want to just keep doing that and it needs to be structured in a way where there are real consequences for them, if they're not being a good citizen, really. (White female, 38 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Well, as I've seen it play out through a few generations now, there's a terrible epidemic of fatherlessness in our society, and I think it plays a huge role in this, a huge role. If I was to put my finger on one source of the problem, I would say that is a very large contributor. (White male, 57 years old, individual property manager and owner)

The moral construction of poverty locates its causes in the perceived poor character of the individual and ignores the racialized social, economic, and political structures under which those individuals exist. A failure in values or morals is then used to explain an individual's impoverished circumstances inversely, meaning that those who are not poor have a higher moral compass. This logic is informed by deficit-based language that then necessitates a paternalistic approach, which aims to regulate the lives of mostly poor mothers.

To some point because the biggest problem we have in North Minneapolis is you do have an applicant coming in and applying for it, and then it's unauthorized occupants because the person who will be moving in will be really, really clean, but once they move in, they'll start getting the trouble. Actually, especially with single moms, that's a bad turn I'm really seeing. (White female, 38 years old, individual property manager and owner)

This landlord, like many others, made note of the role that guests often play in causing discord in the rental relationship. However, in these instances the single mother is determined to be the one without sound judgment, rather than the individual guest. This displaces blame and further stigmatizes single motherhood.

All of the landlords employed some form of value-based judgments when deciding whether or not they would rent to a particular tenant. Value-based judgments often mean that the landlord made a series of assessments about the tenant, their identity, and their values based on racial or ethnic makeup, their family structure, paid work or lack thereof, and purchasing habits to determine if a tenant is responsible and subsequently would be a good tenant. This then explicitly factored into the landlord’s willingness to sign a lease, renew the lease, or pursue eviction when the time comes.

I will not rent to anyone without a job. It doesn't matter if they are on Section 8. My money is getting paid. Even if my full money is getting paid, I will unless they have real disability. I do have two tenants who are on Section 8 who have been my tenants for 3 years. Both of them don’t have jobs, but I know that they are disabled, and I don't have any problems with them. It's good. If I have them on Section 8, my money is being paid, but I've seen people play the system and so if they don't have a job, nope. I don't have a place. (White female, 38 years old, individual property manager and owner)

I probably spend more time than most landlords in screening. I actually go to the family's home. I actually knock on their door and say, "I'd like to see how you keep your present place." So that's always helpful. In fact, many of my good families, actually request me to...They'll say, "I keep a perfect home, a tidy home. Come to my house and I'll show you." That's music to the ears of a landlord. (White male, 60 years old, individual property manager and owner)

I'm getting more and more sensitive to it [UDs]. A UD, on average, costs me $2,000, and that doesn't include anything for my time, and it doesn't include any lost rent that's happening while we're getting the place fixed back up. What I've found over the years is that UDs, once they've had one, they just keep having them. Very few people actually change. (White male, 60 years old, individual property manager and owner)

A lot of landlords are like oh I'm not going to rent to Section 8 anymore. Well, you can't do that here. Or the goofball that bought the threeplex next to me, I'm not going to rent to Black people. I looked at him like “What? You can't do that.” “Well it's my place.” I'm like “I don't care, you can't say I'm not renting to Black people.” (White male, 62 years old, individual property manager and owner)

The last impact of landlords’ perceptions of their tenants is enforcing disciplinary actions. These landlords make assessments of the lifestyles of their tenants and will evict if their tenants’ behavior makes them feel undervalued as a landlord. These landlords see their tenants’ lack of self-discipline or consistency as an opportunity to discipline them for the purpose of ensuring they are more civically responsible. One such landlord described going to a tenant’s house to collect back rent. While at the unit, he noticed a brand-new flat screen TV. He decided to ask about it, and the tenant stated that it was Black Friday. The tenant did not have the back due rent amount that she promised, which the landlord took as a lack of responsibility. He moved to dissolve the relationship.

Many landlords we interviewed had clearly become jaded. One landlord stated that he advised a potential new investor to avoid buying rental property in the city of Minneapolis all together and another landlord had been burned too many times from tenants with evictions on their records and now refuses to rent to them.

I'll answer that question but actually just recently a guy contacted me, cold called me, asking to buy this last remaining property I have in North Minneapolis. After speaking with him, I determined that hey no matter what you offer me, I'm not selling you this property because he's got property in Brooklyn Park and other suburban areas, and this would be his first North Minneapolis property. And I just told him, you don't know the game. You're gonna get screwed and you're just better off staying outside of Minneapolis. And after speaking with him more, he's thankful. He has no interest anymore, going to North Minneapolis, or Minneapolis in general. (White male, 32 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Yes [a tenant will be successful], as long as I don't make an exception for people with evictions. I've done that way too many times. I'm way too nice and it always bites me in the butt. No good deed goes unpunished. (White female, 35 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Section 8 Risk and Reward

For every two jaded landlords, there is one who is consciously aware of how the moral construction of poverty locates the causes of poverty in the perceived poor character of individuals and ignores the social structures under which those individuals exist, especially when it comes to accepting Section 8 voucher holders as tenants. In 2017, the Minneapolis City Council approved a Section 8 anti-discrimination ordinance, which prohibited landlords from refusing to rent to Section 8 voucher holders. If a tenant felt that a landlord refused them because of their voucher status, they could seek damages through the city’s Department of Civil Rights. However, after local landlords challenged the ordinance, a Hennepin County judge struck it down in 2018.

I don't do any Section 8. My rental properties aren't all like this, but they're very nice. I charge probably the upper end of the market for properties, A, because I can and B, you just get people who don't trash the place. So I don't have a lot of UD people or anything else of that nature. (White male, 41 years old, individual property manager and owner)

A lot of landlords embraced the Section 8 voucher program and are astutely aware of the challenges that many tenants face trying to find someone to take their vouchers.

I would say the other challenge is the difficulty of finding a place, so it will have an impact on their rental history. The last four leases I've signed, I believe three involved families that were on their last day of their last extension of their voucher.One was one hour away from losing her voucher. She had to sign the lease and race to Section 8 with that lease. (White male, 60 years old, individual property manager and owner)

The debate among landlords about the politics of accepting Section 8 vouchers is a complex discussion grounded in values and our perceptions of poverty. For the landlords willing to accept Section 8 vouchers, the program will guarantee income each month despite the federal Section 8 housing code guidelines, which can be cumbersome by creating additional checks and balances for the landlord and the tenant. Other landlords outright refuse to accept Section 8 voucher holders because they have predetermined that those who qualify for this program will only damage their properties. Lastly, other landlords express vocal disdain for the Section 8 voucher program not because of the tenants but because of other landlords. They assert that absentee landlords quickly accept Section 8 voucher holders, not caring about the livability issues it creates for neighbors and other landlords. This logic reaffirms the prevalent notion that low-income families are of ill moral character by nature of being poor.

They have the right to double-check and check and stuff. They'll work with you, it's a good thing in a way that it trains inexperienced, absentee landlords that live out in Minnetonka, not to mention any...but just, that's the reality. You've got a lot of investors, “Oh, let's invest in North and put Section 8 or anybody that they find on the street, it doesn't matter because it's North,” they don't live here, they don't care about the livability issues. They'll bring in anybody, and that kind of creates livability issues. (White male, 51 years old, individual property manager and owner)

I really like Section 8. I think it gives you more leverage because if you're not doing what you're supposed to be doing, I can throw you out, or I can get ahold of your case worker and, you know, they have the potential of losing their Section 8 which gives you a little more leverage on, you know, them doing their due diligence as well as me, you know. (White male, 62 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Girl, it goes back and forth. I have some Section 8 tenants that really take care of their property who I have absolutely no problem with. I don't call them, they don't call me. I go over to their house whenever I want to, it's an open door, “Hey Miss Smith, how you doing? You want to come in, have dinner? You busy?” But then you have some who can't even pay $75, and then they get mad at you because, “You already get the majority of my rent. Why do you care about that other $75? You already rich.” Is you serious?...But then you tell them, “Okay, well I'm gonna notify Section 8, and let them know that you ain't gonna pay.” “Okay, [landlord] I'm gonna get it down there to you as soon as possible.” (Black female, [no age given], property manager for a for-profit agency)

Although a majority of the landlords interviewed said that they were willing to work with people who had unlawful detainers or would accept Section 8 vouchers, the manner in which they perceived tenants influenced the amount of risk they would take on future tenants. A number of landlords would not rent to anyone with an unlawful detainer. One in particular talked about knowing landlords who have explicitly stated that they would not rent to Black people, or rent to anyone with an unlawful detainer. Another stated he takes into account the condition of the interior of his potential tenants’ cars as a reflection on their potential tenancy.

This moral constructionist framework has been written into our public policy framework. A prominent and deeply embedded example came from the Moynihan Report of 1965, officially titled “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” published by the Office of Policy Planning and Research through the US Department of Labor. Former Senator David Patrick Moynihan argued that although the history of slavery had grave effects on the Black family structure, it was in fact the lack of a Black male patriarch and the large number of Black, female, single-headed households that was the source of economic deprivation in the Black family. This “blame the victim” approach to a lack of “proper” nuclear family structure presumed a lack of values and the willful perpetuation of poverty. The perception of poverty and a few bad experiences with tenants can structure how landlords develop and implement strategies for mitigating loss that are often informed by factors such as a tenant’s race or job status, in turn determining a tenant’s level of responsibility or worthiness and decreasing their willingness to work with other tenants in the future.

Strategies for Mitigating Loss

The most common approaches used to mitigate loss by the landlords interviewed were cash for keys, mutual termination of lease by nonrenewal, and signing only month-to-month leases.

Cash for Keys

Cash for keys was a somewhat contentious topic for the landlords interviewed. One landlord stated explicitly that she was completely against offering tenants cash for keys, because she wants people’s choices to have consequences. Whereas others did not use the practice had no established opinion about the tactic, had never even heard of it, or had never gotten to the point where they thought it was a tactic worth using.

For those who have used and are still actively utilizing the tactic, they determined that they would spend less money offering tenants cash for keys than the entire cost of the eviction process. These landlords were also attempting to prevent the loss of income, because of the time and resources associated with the unpredictable Housing Court process. One property manager explained that offering tenants cash for keys might very well “kill” the property owner, who must come up with $500 out of pocket to get someone out, but the cost of filing an eviction is too high.

The process often includes hiring a lawyer, only to be encouraged to “work it out” at court, which could result in an agreement that the tenant does not fulfill. Then the owner would have to file a writ to physically remove the tenants, all of which they determined could cost over $2,000 and a lot of wasted time, despite the fact that very few evictions often end in a writ being filed.

It's anything you can think of, of what they would say back. Like, you'd say, “You know what? What if we come there with, $200. Today, you sign the paperwork, and when we confirm you've moved out, here's another $200.” Or, whatever dollar amount you can put in there. I think probably, in that scenario, we wouldn't talk about the security deposit, because you'd just assume it's lost. You're not getting it back. They've already made that assumption. (White female, 39 years old, property manager for a for-profit housing organization)

I almost always actually do a cash for keys option before I do the eviction. I say, “If you're out by X date, then I will give you $500 cash,” just end of story. (White female, 35 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Mutual Termination of Lease

Mutual termination of lease is used most commonly for two reasons: either as a result of domestic violence and lease violations, or landlords will simply not renew the lease at the end of the term. Other landlords reported never needing to use it, because tenants, as one landlord stated, will “up and leave” without notice, preempting an eviction due to a lack of respect, or communication has taken place causing a strain on the relationship.

We always offer it [mutual termination]. The eviction process is so expensive and cumbersome, and it's such a big deal to do an eviction, that I try to avoid it at all costs...That's usually when I'm about to get ready to file for an eviction, I say, “I have to file for an eviction, unless you are out on this date at this time, for this amount of money.” And I typically also offer it throughout the eviction process. It's usually a 60-day, sometimes we'll just serve a 60-day notice that we're not renewing the lease, because our leases are all 12 months, and then month-to-month thereafter, with a 60-day notice. (White female, 35 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Okay, so first stage of it is trying to negotiate a mutual term termination lease or mutual lease termination. Mine looks like, “Okay, you are not paying rent anymore, pick a date, hand in the keys. We don't want that date to be more than 3 weeks out,” we won't go that far. About 3 weeks I want to see the keys back and kind of done...A lot of the time. I would say at least 90% of time, we can do it.(Black female, 44 years old, property manager for a nonprofit organization)

The Month-to-Month Landlord: An Underanalyzed Predatory Practice

The month-to-month strategy for mitigating loss is an underanalyzed yet powerful tool for landlords in managing risk. Landlords can mitigate their risk by offering a short timeline that allows for a nonrenewal of lease quickly if tenants do not adhere to their lease expectations. Additionally, landlords can protect their ability to profit from a hot housing market by having the option to evict tenants through nonrenewal quickly. Although the Section 8 program requires a year lease, tenants who rent in the private market without a government subsidy are subject to a landlord’s lease parameters, which may increase housing precarity.

Of the 32 landlords interviewed, 50% (16) noted offering month-to-month leases, with 2 noting that they only offer month-to-month leases unless dealing with Section 8 voucher holders.

Now here's how I defend myself. Unless you're Section 8, I only use a month-to-month lease. Because if I misjudge, and I get 3 or 4 months in, and you're just not paying, then I can say, “I am not renewing your lease as of,” whatever date. I have to give them minimum a month, and a day. That's a safeguard for me. (White male, 58 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Tell them [renters outside his network] we're gonna do a 6-month contract. After that they all become month to month...I'll give them 2 months' notice and then you're out just in case I need it for somebody else or whatever, if I need to sell the property or something. I've been tempted by the real estate prices to sell some of them. Out of all the people that I have right now, they're all month to month. (Latino male, 34 years old, individual property manager and owner)

In addition to these three common strategies for mitigating loss, the landlords we interviewed used other less-common methods as well. The least common approaches were double deposits and lack of cleanliness. Of the 68 tenants interviewed, only 16% (11) reported paying a double deposit, thus supporting this statement. For the few landlords who utilize double deposits for tenants they deem to be “risky,” they believe that a tenant is more likely to be a “good” tenant if they want to receive their double deposit back. However, one landlord stated that in the past he required double deposits and tenants failed to meet the payment plan they had arranged. This instance refuted for him that a double deposit is any incentive to ensure that tenants will fulfill their lease agreements. Additionally, one landlord stated that when tenants come with a housing voucher and do not have to pay the deposit themselves,they have no “skin in the game.” This landlord then automatically expects that the tenant will not be successful.

When a tenant actually comes up with that money (double deposit) themselves rather than an agency...those are usually your better tenants, 'cause they know their money can go back to them if they do the right thing. (White male, 63 years old, individual property manager and owner)

My current property manager is making sure he's a very strong-willed individual, who just makes absolutely sure that they understand that garbage is supposed to be taken care of, the streets are swept. If your house is not in order, we will ask you to leave. We've come across, very often, where people just don't have any cleanliness in their lives, and we will not tolerate that. Cleanliness and order. (White male, 64 years old, individual property manager and owner)

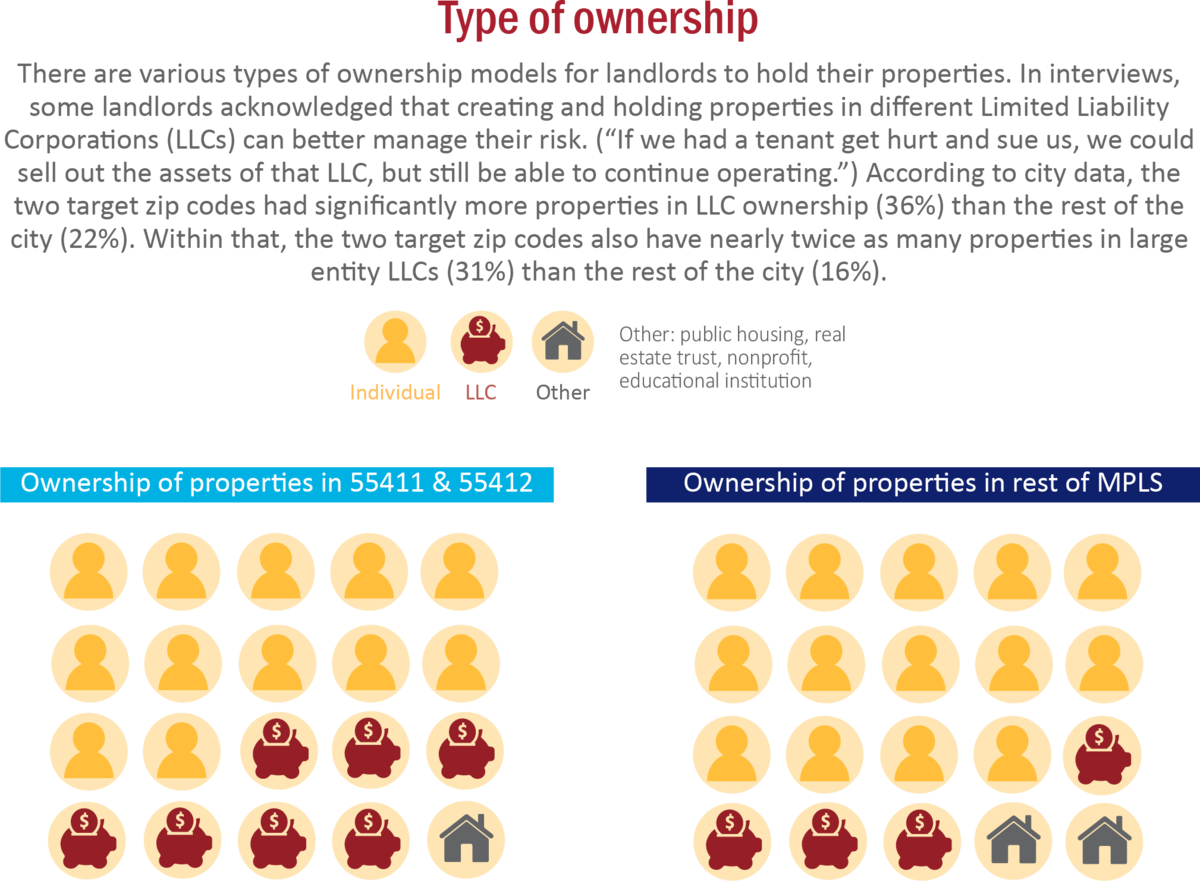

The Rise of the LLC

Nearly twice as many properties in North Minneapolis were owned by large-scale limited liability companies (LLCs) (31%) compared to the rest of the city (16%). The LLC ownership structure allows landlords to shield theirpersonal assets and makes identifying ownership and legal responsibility difficult.

All of our homes are owned by LLCs. There's usually two or three houses per LLC, so usually that profit has extra capital from the other properties within it...That's partially for some of our online ability, if we had a tenant get hurt and sue us, we could sell out the assets of that LLC but still be able to continue operating.(White female, 35 years old, individual property manager and owner)

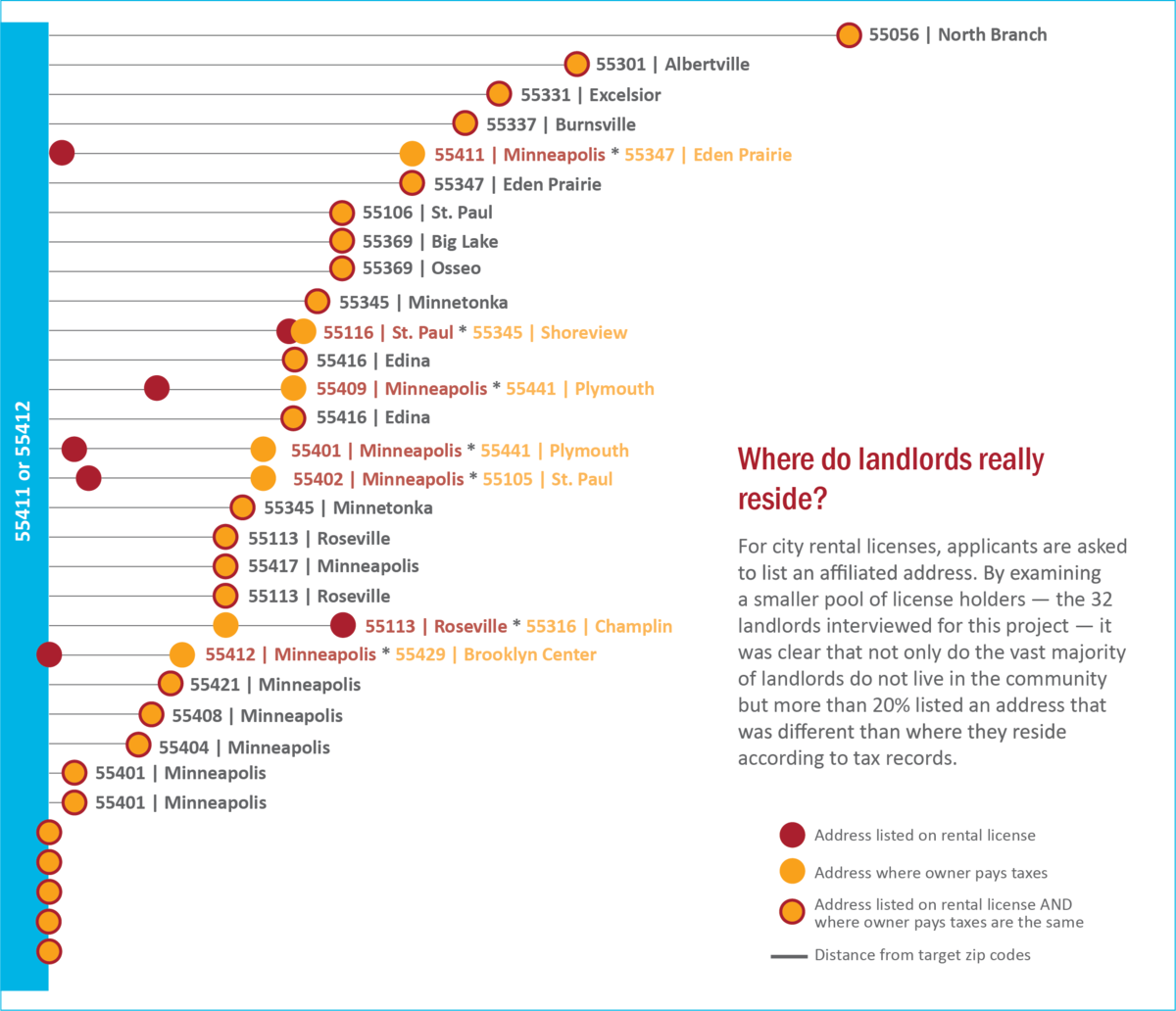

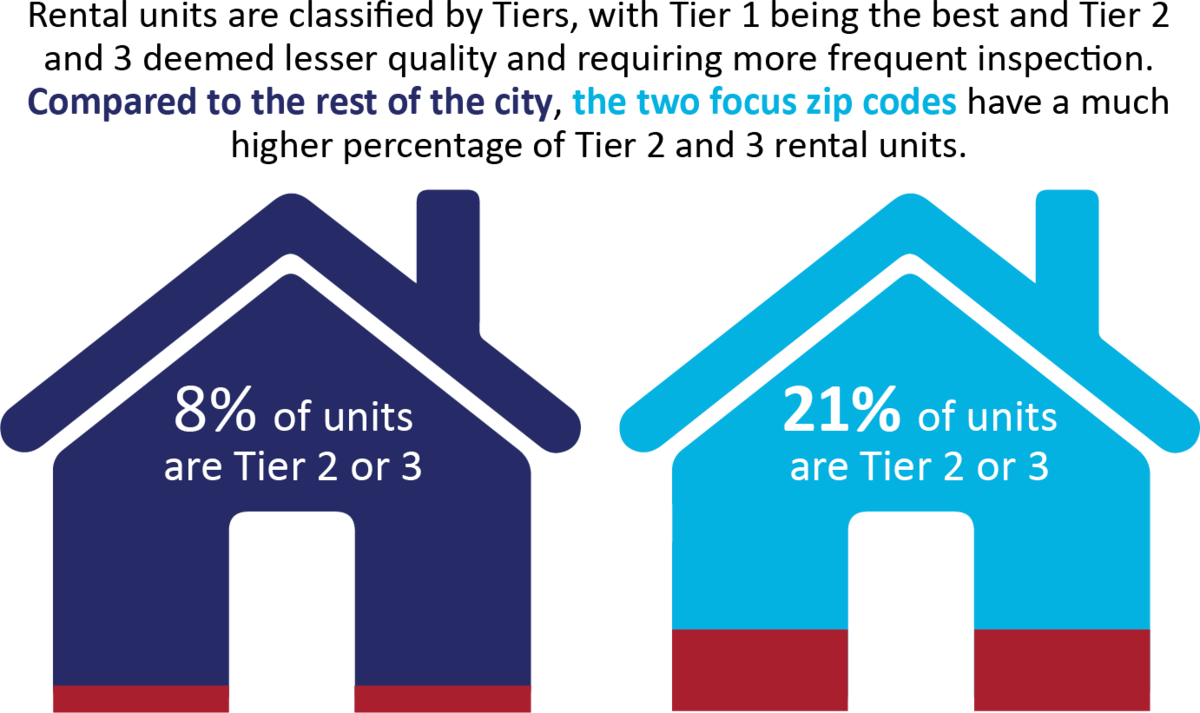

Only 5 of the 32 interviewed landlords list an address on their rental license or pay taxes on a home in the two focus zip codes. In the two focus zip codes overall, only 9% of units are owner occupied, compared to 21% in the rest of the city.

In research on landlord investment strategies and the link to property disinvestment in Milwaukee, WI, Adam Travis (2019) argues that across the last two decades, investors are moving toward the LLC model of ownership to limit individual liability. He found a correlation between the LLC ownership trend and properties that are not up to code, a trend seen most often in cities’ poorest distressed neighborhoods. Travis states that this trend has taken place because of advances in the legal environment since the 1990s with the creation of LLCs, which “promises to ensure that personal assets will be protected from business-related liabilities” (p. 143).

The evictions research team spent a significant amount of time trying to distinguish individual ownership from LLC ownership structures in North Minneapolis to understand where landlords reside in relation to their properties. This work just scratched the surface of the relationship between individuals and LLCs in North Minneapolis. A closer examination of data in the city of Minneapolis must take place to determine the correlation between increasingly distressed properties and their code violations and the ownership structures, which may provide protection for these landlords.

Where do landlords really reside?

The Intersection of Nonprofits, Subsidized Housing Programs, and the State: Small-Scale Landlords in North Minneapolis

Denise has been a landlord for 19 years and for the last 11 years has managed for a nonprofit organization. Like a majority of nonprofit housing landlords in this project, Denise stated that she fell into this line of work starting off first as a leasing agent in market-rate properties. She left the market rate industry because it was too corporate. She felt the industry was only in it for the money, and as a result, many tenants would end up homeless or having to move without anyone caring. Instead, in the nonprofit sector, “We tend to choose to house populations with the largest barriers. We choose communities where we can make a difference or where change is needed.”

Denise manages over 200 units of housing in North Minneapolis. The nonprofit housing provider conducts criminal background, credit, and rental history checks and requires no unlawful detainers in the last 2 years. The organization works with several homeless programs, so they expect to see some UDs and they provide a program for tenants with UDs to become eligible for housing. Additionally, although they cannot work with arsonists and sex offenders, they do work with felons as part of a supporting housing program in North Minneapolis. Finally, the organization has processes that veer from its criteria and may grant tenancy to people who were initially denied. Most of the tenants granted residency after denial are working with a supportive agency and with the organization to create stability.

Denise does not believe there is a good way to predict the success of a tenant. She sees screening criteria as how landlords try to predict and mitigate their risk. However, a tenant can look stellar on paper but be a horrible tenant or look horrible on paper and be a really good tenant. Denise stated that screening criteria are just used as a mechanism to ensure access to fair housing, but it is not the best way to determine an applicant’s success.

Denise’s organization has a structured process regarding evictions. The organization requires first month’s rent and a security deposit prior to moving in but will accept a guarantee letter from a support agency in lieu of money in hand. The organization modestly increases rents annually, between $10 and $15. Every tenant gets a notice of rent due on the first of the month, and then between the sixth and the tenth, the resident will get a 10-day late rent letter. Tenants who are late have the option to either sign a mutual termination to move out or arrange a payment plan. If they do not hear back from a tenant after this letter, the organization must decide if it will pursue eviction.

If the tenant is having conduct issues, not nonpayment issues, the organization almost always pursues mutual termination, because it believes that just because the tenant is not successful with them doesn’t mean they won’t be successful elsewhere. The organization doesn’t want to create another barrier with an unlawful detainer. Additionally, it gives a neutral rental reference. Denise knows that this angers other private landlords.

In Denise’s opinion, the challenge that most of the tenants face is affordability. She notes that 90% of those they present with mutual termination accept it, because it will look unfavorable to another landlord to receive an unlawful detainer from a mission-based organization like hers. When tenants lose an income and are without any means to pay, they will simply get farther and farther behind, therefore, mutual termination is pursued first if no resources are available to assist them. This organization budgets for evictions, and Denise supports unlawful detainer expungements and will not appear in court to fight it if a tenant files for one.

For Denise’s organization, the courts can be challenging, especially when filing for a lease violation because the burden of proof is on the landlord, and particularly when the city is forcing the organization to evict someone and it asks for a trial. The process becomes long and drawn out because circumstances are hard to prove. It's quite difficult to get tenants removed, and the organization has fought cases for months, draining limited institutional resources.

Because Denise’s organization provides affordable housing and has tax credits, it’s impossible to simply not renew a lease like private landlords. There must be a cause for not renewing a lease. The burden of proof is on the organization. In those instances where the organization knows that it could file an eviction, but wants to make another last-ditch effort to work with the tenant, it develops an individualized eviction prevention plan for the tenant with management and within the terms of the lease. The plan outlines what actions the tenant will agree to, to ensure the behavior will not continue to happen. If this agreement is violated, the tenant will be asked to leave.

Denise, like many other nonprofit housing managers, believes deeply that the work assisting those families with the largest barriers to obtaining housing is critically important. These agencies’ missions require that they set up mechanisms to support tenants during hard times and provide them access to services.

The owners...Out of these three entities in the zip codes, one of the entities is a nonprofit. So, it makes things a lot more...It makes things a lot easier. Where the other two are not nonprofits, but they are not looking to take income from the building to pay their mortgage. But they are looking to take income out...Income from the buildings...So, I think the receivables. Right, so if you look at the end of the month receivables, that they're rate of two people haven't paid rent for the month, they're [nonprofits] more willing to be understanding. (White male, 50 years old, property manager for a for-profit company)

They're [nonprofits] a little more altruistic in their endeavor than a private landlord. They're looking at properties...On their side, too, they're looking to rehab properties using the Section 42 program. They get developer fees out of that. They also, they're specifically targeting affordable housing and looking at those areas where there's properties in distress, which is going to be more difficult. (White male, 32 years old, property manager for for-profit company)

The units that have service providers are my most successful households. When they're not and there's an issue, the service provider steps in and either gets the tenant or the tenant no longer receives services. (White male, 50 years old, property manager for a for-profit company)

Nonprofit Organizations and Subsidized Housing

Undoubtedly, nonprofit organizations and subsidized housing opportunities play a critical role in providing housing, economic, and social support to residents of North Minneapolis. Additionally, nonprofit housing agencies are seen as the altruistic affordable housing conduit for those low-income families and seniors who cannot afford the traditional market-rate housing options. Concurrently, these residents’ backgrounds often prevent them from appearing as ideal candidates. Yet, the overrepresentation of nonprofits and housing subsidies in these two zip codes create a tension between the high need for safe, affordable, and quality housing units and the potential paternalistic dependency on affordable housing to maintain housing stability.

According to the City Planning and Economic Development (CPED) office in Minneapolis, nonprofits have fueled a majority of the new construction and some rehabilitation in North Minneapolis, based on CPED funding and public-owned land sales. Over the last 7 years, at least nine different nonprofit housing organizations have been involved in new development projects in North Minneapolis. The neighborhood has received little large-scale, new private housing development that has not been built by a nonprofit housing agency, and as a result there's little research that proves that market-rate rents would be successful. In many ways, this reflects the disproportionate rate of low-income residents of color in North Minneapolis. Nonprofit housing developers as well as subsidized housing opportunities match the resident type, in that these resources are clearly designed to provide support for housing-insecure residents.

Ours [criteria] is already pretty low. I think though because we're mission-based, the financial cost of business...being mission-based is pretty steep. Because we're choosing to create housing stability or help folks create housing stability, we go above and beyond. We don't file a UD unless it's absolutely necessary. We put things in place, like an eviction prevention plan and try to work with you to get you to curb your behavior that's causing the problem. (Black female, 44 years old, property manager for a nonprofit organization)

Yet, landlords questioned whether or not these types of support are just reiterating a cycle of housing instability—a shallow and temporary solution that provides subsidies to landlords but does not get to the root of the barriers to helping tenants reach housing stability.

I'm gonna be honest with you. I don't know, because I got some people they get out the shelters, and they've been with me for 5, 6 years. They're not on any rental assistance, they pay their rent, do you know what I'm saying? I guess a lot of them, they come from the shelter, after their assistance is over they feel like their life is over, and they're right back in the shelter. (Black female, [no age given], property manager for a for-profit organization)

I think the best way is, obviously, when people are willing, they get back on their feet. Because, people moving around, isn't helping anybody. Getting them back on their feet would be the best way, but doing that is obviously not our...We don't know how to do that. I mean, we try. (White female, 39 years old, property manager for a for-profit organization)

Landlords benefit from the subsidies provided to North Minneapolis residents. An example of this came in an interview with one of the landlords who was noted by the Minneapolis Innovation Team’s (2016) report as a frequent filer. Although he provides housing to Section 8 voucher holders, this landlord openly spoke about his use of eviction filings. He benefits from state-sponsored housing subsidies, yet his tenants pay the price with multiple eviction filings.

I believe there was something that was on public radio; they talked to the reporter about a month ago. When he ran the story I pulled it up. I think I had 67 that were filed (formal evictions) in the last, I think it was 3 years. To be honest with you, I think it's a little more than that. I would have to say it's more like about 40 a year. And granted, it doesn't mean they actually end up moving, but it's just that many are filed. (White male, 68 years old, individual property manager and owner)

The Minneapolis Public Housing Authority (MPHA) is a strong example of the tension between providing much needed shelter and reinforcing a cycle of paternalistic dependency. Historically, public housing developments were built in the central city, particularly in low-income communities of color. North Minneapolis is no exception. The MPHA, a quasi-governmental agency, provides almost 6,000 units of public housing across the city of Minneapolis, with approximately 19% (1,163) of these units in the 55411 and 55412 zip codes, specifically. Yet, according to the MPHA, there are approximately 7,000 individuals and families on the waitlist for high-rise buildings, mostly the elderly and disabled, and close to 1,000 families are waiting for other housing options. The lack of housing available to residents outside of the MPHA and other nonprofit housing providers creates a dependency, leaving residents little choice but to abide by MPHA rules or risk losing their only option for stable housing.

I think some of the people who might be less successful are the people who are homeless, ‘cause they come into our situation and now they're...We have rules, about your behavior and paying rent and all that stuff and so I think that it seems to us that the people are homeless, like the goal is to get them housed but then their services kinda drop off. Now we do have social workers through the Volunteers of America in the buildings, and so we really are working toward helping people be successful tenants and so, anytime we send out a nonpayment letter, the copy of the spreadsheet goes to the Volunteers of America social workers and all of our staff, we're trying to knock on doors, get people to pay their rent, so that's in the first month. (MPHA staff member)

When nonprofit and low-income housing subsidies become the last resort to stable housing, the impact of evictions becomes that much more relevant. Although they play a critical role in North Minneapolis, the mission of housing stability is threatened by a cycle that reinforces dependency and lacks the resources to help residents move to full independence.

The Role of Housing Support Agencies

Private landlords did not express any explicit opinions about nonprofit housing other than to send the message that they were not “going to be Mary Jo Copeland,” which aimed to ensure that people understood that they got into real estate investment to make money. However, a small number of private landlords called out the contradictions embedded in the short-term housing subsidies programs that many participate in, and as a result many now seriously question the social services system.

The program that I've done the most work with is St. Stephens and the short-term program doesn't work at all. As soon as they're on their own, they start falling behind. Every single one of those people have had to be evicted. Doesn't work and the long-term program doesn't really work either because they're putting people in...It's like they're sneaking people in that they know are drug addicts, who are gonna turn your house into a flop house, so yeah the rent’s paid, but they're doing damages, they're causing problems with the neighbors, a lot of problems. Initially, I was really excited about the program because they say that they check in every week with the tenants, but there's no real consequences with the tenant, so they can check in, but the tenants start doing what they're doing. (White female, 35 years old, individual property manager and owner)

They reached out to me. I put an ad on Craigslist and they reached out to me. They said that they would pay the rent in full, for a year, for this particular person. And obviously that sounds great, so I did that. I don't know how this is legal either because they signed a lease saying that they would do that. I know I signed a slew of other paperwork but then as the income changed their payments to me changed as well...It actually incentivized the tenant not to work in a lot of cases. And then Simpson Housing their funding eventually runs out. And the landlords are stuck with the tenants. And they're broke. And they leave all their stuff behind again. (White male, 32 years old, individual property manager and owner)

Not all landlords reported bad experiences with these housing subsidy programs. Yet, clearly many did not understand what it meant to support a program that aims to house families with significant barriers. Additionally, most, if not all, of the landlords who have participated in these programs stated that short-term housing subsidies are only temporary bandaids that free up beds at the county shelter. This draws attention to how our county system is in fact not doing the work of helping to stabilize families but rather focusing on the cost per bed, forcing families back into a state of constant crisis decision making, which leads them back to the shelter.

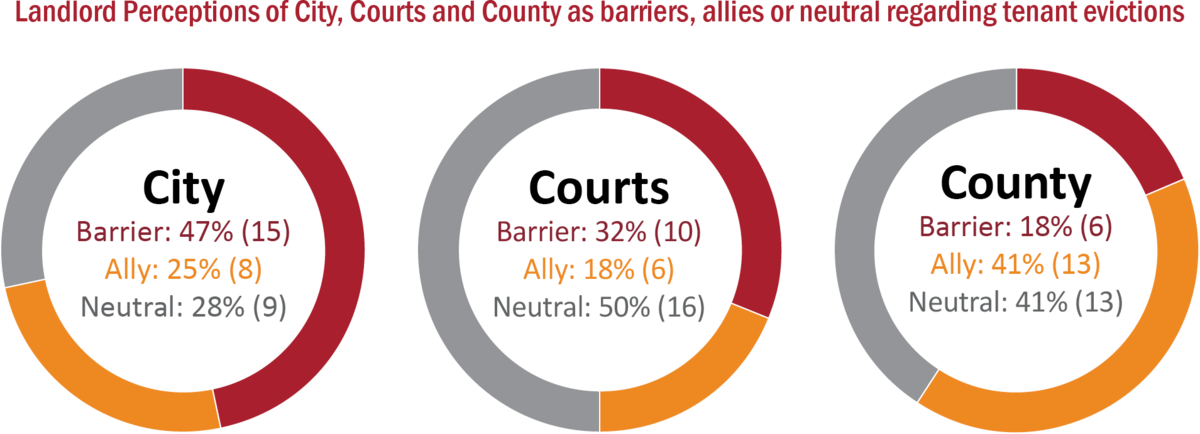

Landlord Perspectives on the City, the County, and the Courts