There is a fear premium attached to North Minneapolis. Because what’s the stereotypical image people have of North Minneapolis? I could tell you. Bang, bang. People are afraid of it. If you tell people, I bought a property in North Minneapolis. What they say is, “Why would you do that?” (White male, 58 years old, property manager and owner)

I've heard bad things. He's known as a slumlord...But against my better judgment, to not wanting to be out a place and homeless and between moving, I took the first thing. It was like a desperate situation. (Biracial female, 45 years old)

I think that it definitely has to be made a law that a UD should not go on a person's name until after you have been found guilty in court. It is horrific that you would sit up here and have a UD on my name that prevents me from moving...You would rather a person be homeless than to give them a day in court to be heard first...You shouldn't have to be homeless to be heard. (Biracial female, 36 years old)

What must we understand about the intersection of affordable housing, economics, and Black women in North Minneapolis?

North Minneapolis is experiencing the social crisis of evictions. The neighborhood is designated as a racially concentrated area of poverty. It was created after decades of disinvestment and neglect from radical de-industrialization, White flight, racially segregated public housing, redlining, and blockbusting by unscrupulous real estate agents supported by Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage policies and practices. Today, North Minneapolis is described as a place to “escape from” because of its popular depiction as a dilapidated inner-city community riddled by Black poverty, high unemployment, poor-performing schools, oppressive policing, and segregated housing, which have endured over time. Both strategic city and state policies and racial prejudice have created a highly segregated portion of the city with one of the worst achievement and unemployment gaps between Blacks and Whites in the nation.

Black women in Minnesota, and North Minneapolis more specifically, are faced with an economic crisis that has gone unaddressed for far too long. A study completed by Algernon Austin of the Economic Policy Institute called Uneven Pain—Unemployment by Metropolitan Area and Race found that in 2009, during the height of the recession, the Black unemployment rate in Minneapolis and Detroit was over 20%. In the case of Minneapolis, the Black unemployment rate was three times the White rate. In March of 2011, Randy Furst with the Minneapolis Star Tribune confirmed these statistics by reporting that the Black jobless rate in the Twin Cities was at 22%, 3.4 times the White rate of 6.4%. However, the disaggregation of the data by sex shows that at the height of the economic recession, Black women's unemployment in the state of Minnesota was slightly higher than that of Black men. Additionally, single Black women with children living below the poverty line lead more than 60% of the Black households in North Minneapolis. As a result, 67% of residents are on some kind of county and federal government assistance, living one financial crisis away from losing their homes (Lewis, 2015).

Housing is at the center of family stability. Currently, the city of Minneapolis is experiencing a housing crisis with a 4% vacancy rate, causing families to confront a challenging housing market where rent has increased 28% across the Twin Cities since 2007, disproportionately impacting Black women and their families.

Why does CURA do this work, and why is it important to center the voices?

At CURA we believe that fair housing is about choice. We believe that all people should have full and equal access to the housing market, with the option to live in the communities they desire. In the case of North Minneapolis, we believe that despite the popular fair housing rhetoric, communities of color see value in their neighborhood and resist the stigmatization that claims their communities are only places to escape from. Rather, North Minneapolis residents are proud of their communities. The challenges that exist are a result of housing discrimination, decades of urban disinvestment, unfair lending practices, disproportionate evictions, the racism behind differential social services, and the realities of poverty and unemployment. These exploitative systemic realities are why some from the community might decide to disengage, even if they continue to see the value in their neighborhood. As such, it is critical that we center the voices of those most impacted by our discriminatory housing practices, because they are the experts on housing injustice in this country.

What is the problem?

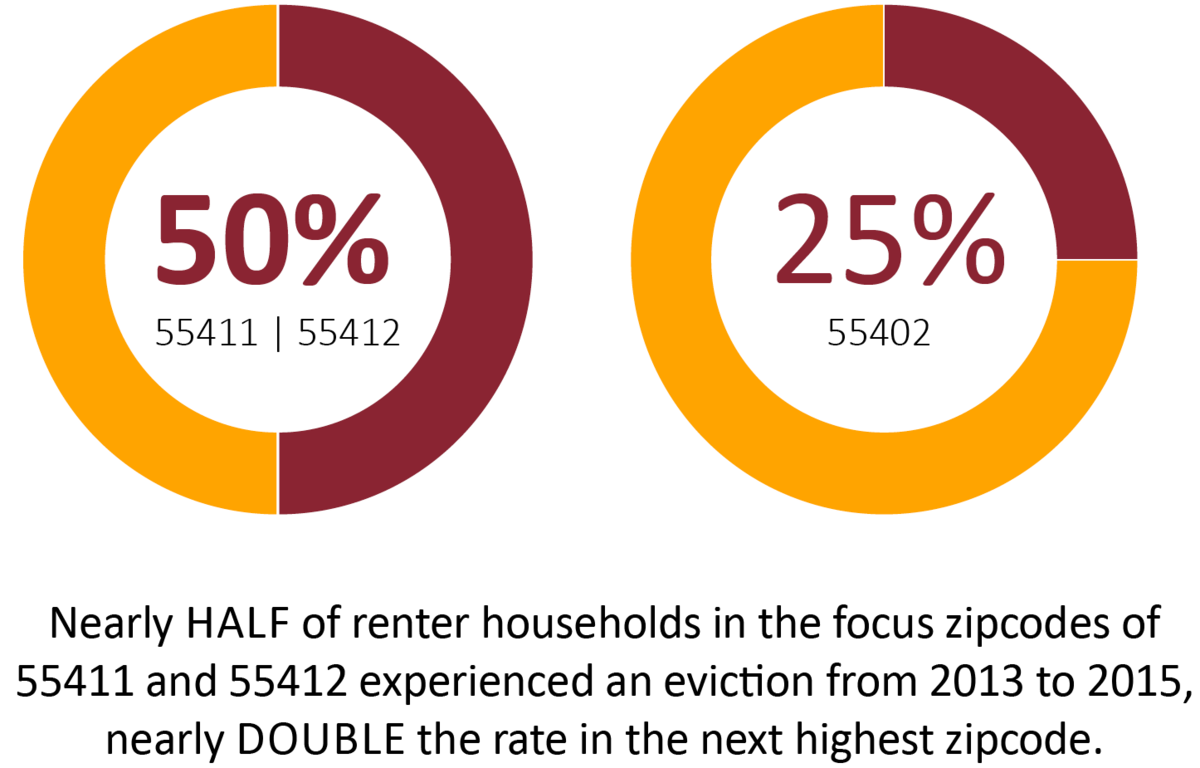

In July of 2016 the Minneapolis Innovation Team’s Evictions in Minneapolis report found that from 2013-2015, approximately 50% of renter households in North Minneapolis experienced at least one eviction filing, a rate that is almost 25% higher than the 55402 zip code, which experienced the next highest rate of eviction filings in the City of Minneapolis. This disparity is particularly relevant given that these two zip codes contain just 8% of all rental units in the city, that an eviction action stays on a tenant’s record for an average of 7 years, and that a tenant is four times less likely to use homeless shelters if they had legal representation (Minneapolis Innovation Team, 2016). An exit survey conducted in the summer of 2017 by Hennepin County staff from the Office of Housing Instability at Housing Court found that Black women are disproportionately affected by evictions (55%), which further supports Dr. Matthew Desmond's claim that if incarceration has come to define the lives of men from impoverished Black neighborhoods, eviction is shaping the lives of Black women (Desmond, 2012; 2016). An eviction action, commonly known as an unlawful detainer (UD), is now akin to having a criminal background, preventing Black women from attaining safe and affordable housing for themselves and their families.

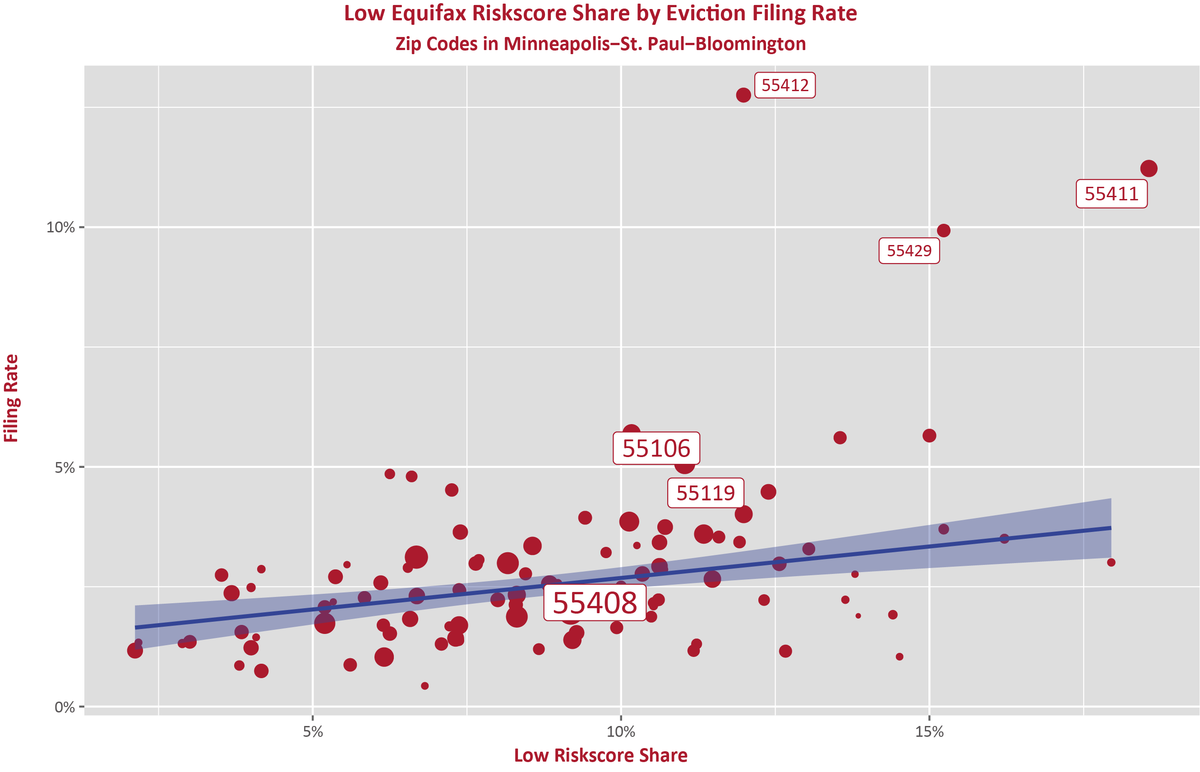

These trends, disproportionately represented in certain zip codes, require us to consider different approaches and ask different questions to analyze the realities of renters. Yet renters are often overlooked in quantitative data analysis, in part because of the lack of individualized data available through tools such as US Census data. To isolate renters, we cross-analyzed national Evictions Lab and Equifax Credit data, where we made a distinction between nonmortgage holders and mortgage holders. This data illustrated a clear disparity between eviction filings by zip codes and shares of credit risk scores, alluding to disproportionate filing practices across low-wealth neighborhoods compared to nearby affluent neighborhoods.

The blue line in the figure is what you would expect to see for the average rate of eviction filings based on credit risk scores across the Minneapolis, St.Paul, and Bloomington areas. The zip code 55408, a more affluent area with a higher rental population (noted by a larger circle) extending from Uptown to Powderhorn Park in Minneapolis, represents what one would expect to see for eviction filings versus credit risk score. Two of the other zip codes highlighted, 55106 and 55119 on the Eastside of St. Paul, represent areas with higher risk yet fall close to the expected eviction filing. However, the filing rates for North Minneapolis, specifically 55411 and 55412, which have lower renter populations compared to the 55408 zip code, deviate significantly from what would be expected. Beyond the scope of this report, 55429 in Brooklyn Center was identified as an extreme outlier. This illustrates the potential for outlier filing behavior in the two North Minneapolis zip codes.

An eviction, also known as an unlawful detainer (UD), often elicits the vision of a sheriff knocking on a family’s door with a writ of eviction and a group of workers removing and placing a family’s belongings on the curb. In its narrowest form, an eviction can be described as the forced removal from someone’s home. In reality, evictions in the United States are much more complex. The threat of an eviction filing or repeated eviction filings have become tools in the landlord-tenant power dynamic, even when they do not result in a tenant vacating the home (Immergluck et al., 2019). In fact only 22% (15) of tenants interviewed had a writ of removal issued (i.e., the sheriff coming to forcibly remove the tenant from the home). A more holistic definition of an eviction filing includes “any involuntary move that is a consequence of a landlord-generated change or threat of change in the conditions of occupancy of a housing unit” (Hartman and Robinson, 2003, p. 466).

For low-income people and people of color across the country and in Minneapolis, evictions pose a significant barrier to accessing and maintaining quality, stable housing. Not only is a forced move destabilizing for households but having an eviction (i.e., UD) on your rental record is also a major barrier to accessing future housing, especially when the available Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing (NOAH) is often of lower quality. Single Black mothers face the highest risk of eviction in the United States (Desmond, 2012; Hartman and Robinson, 2003). Housing instability and displacement puts these women and their families at risk for a myriad of social, political, and economic hardships. Mothers who experience eviction and housing displacement are much more likely than their housing-stable counterparts to experience negative health outcomes, not only for themselves but their children. (Desmond and Kimbro, 2015).

Why an actionable research study on evictions in North Minneapolis?

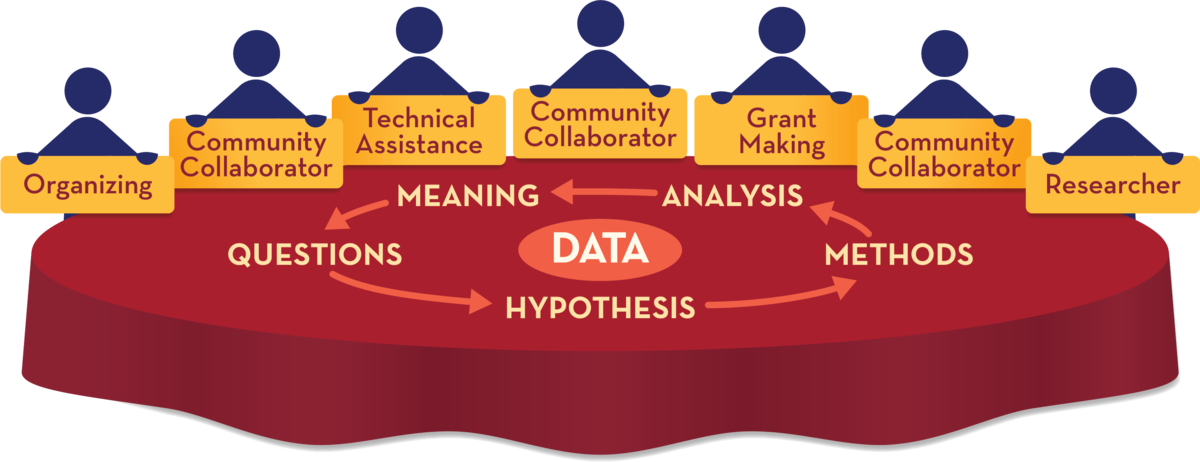

CURA and its community partners value the quantitative research study by the Minneapolis Innovation Team in 2016, but we collectively found that it did not answer the critical questions of why and how these trends were taking place from the perspectives of tenants and landlords themselves. Senior Research Associate Dr. Brittany Lewis’s actionable research model stays committed to the idea that the only way to successfully develop public policy solutions and innovative programmatic interventions is to center the voices of those tenants that are most negatively impacted by evictions and the landlords investing in these local communities, because they are our most valuable sources of knowledge in the study of evictions.

Researchers committed to community-engaged action research must fundamentally believe that the communities we work with are the experts on their own realities. This is particularly important for low-income Black women, whose knowledge of the social, political, and economic world has been deemed unimportant and irrelevant (Stabile, 2006). Popular media and elected officials regularly shame and blame low-income Black mothers for their experiences of poverty. This is evidenced in derogatory popular images such as the “welfare queen” and inscribed in policy “reforms” that aim to discipline the poor (Alexander-Floyd, 2007; Hancock, 2004; Jordan-Zachery, 2009). Community-engaged action research values community knowledge and people’s lived experiences. The model reflects meaningful collaboration between academics, advocates, policymakers, service providers, and impacted communities. Additionally, it leads to more robust and holistic data, more effective policy solutions, and stronger community action. When we use a community-based action research model, community members are not the subjects of research, they are the co-producers of knowledge.

In 2017, under the leadership of Dr. Lewis, CURA launched an in-depth qualitative research study of evictions in North Minneapolis with the local community as co-collaborators. The purpose of the project was twofold: (1) to gain a clearer understanding of housing composition and stability over time, as well as various income streams of tenants who have experienced an eviction filing, to help better inform the development of targeted interventions, needs, and policy prescriptions and (2) to gather data to better inform the ways that the city and state can work with landlords as partners in community building. Dr. Lewis and her team utilized a community-engaged actionable research model that aims to use research to:

- build community power;

- assist local grassroots campaigns and local power brokers in reframing the dominant narrative;

- produce community-centered public policy solutions that are winnable.

This model relies heavily on building reciprocal relationships across sectors that embrace an open process where the collective develops shared understandings for the purpose of creating social transformation. This actionable research model embraces a racial equity framework that asserts that we must:

- look for solutions that address systemic inequities;

- work collaboratively with affected communities;

- add solutions that are commensurate with the cause of inequity.

For The Illusion of Choice project, CURA and its community partners co-developed an in-depth qualitative research project that included 100 tenant and landlord interviews in the 55411 and 55412 zip codes in North Minneapolis. In conjunction with a number of supportive, actionable research strategies and tools, the project not only created primary source data on evictions but also used that data as a tool of action to inform, influence, and transform public policy discussions and action across the state of Minnesota.