Yeah. I just went to Hennepin County and yeah, they gave me to some rapid re-housing counselor, or something like that. But she kept telling me I needed to...She said, "Is there anything wrong with you?" I was like no, I'm just a normal person that lost their job. She wanted to know if I was a domestic violence victim. She wanted to know if I had mental health issues. She wanted to know if I was using drugs. Which, all of the above, but I was too embarrassed to share it with her. You know? I didn't want nobody to know I was using drugs. You know what I'm saying? I'm not anymore, I'm proud of that. But I overcame it. But I didn't want nobody to know that I was using drugs. So, I told her no. So, at that point, they couldn't help me, because something needed to be wrong with me for them to get me housing right away. (Black female, 55 years old)

Tenants

The Social Service Runaround: Differential Treatment

What Is the Social Service Runaround?

When tenants were interviewed, it was quite common for them to describe their experience of applying for Hennepin County emergency assistance as “dehumanizing” and show emotional anguish or often cry. Interviewees would go further and state that when they were in the process of applying and seeking support, they felt they were given the “runaround.” In short, the runaround was quite literally the process of collecting the forms, paperwork, and permissions at different places, within a frame of limited information. For example, tenants were often told after the fact that they needed a formal eviction filing to be eligible for services, forcing them to “run around” between social services, Housing Court, and property managers to gather the paperwork needed to even apply for support services.

The results of the tenant interviews and our analysis of their findings necessitated the creation of this social service runaround section, which is arranged to examine three major themes: (1) the politics of dehumanization, (2) discrimination against single people, and (3) the “dollar over” club. The three themes are each examined, starting with a short case study and followed by the emerging concepts, as evidenced by the actual statements made by tenants in their interviews (throughout, names of interviewees have been changed to protect their identities). Finally, we end with a summation of how the themes examined in context relate back to how and why eviction trends are taking place in North Minneapolis, from the perspectives of tenants and social service navigators as they reflect on the impact that the social service system has on evictions.

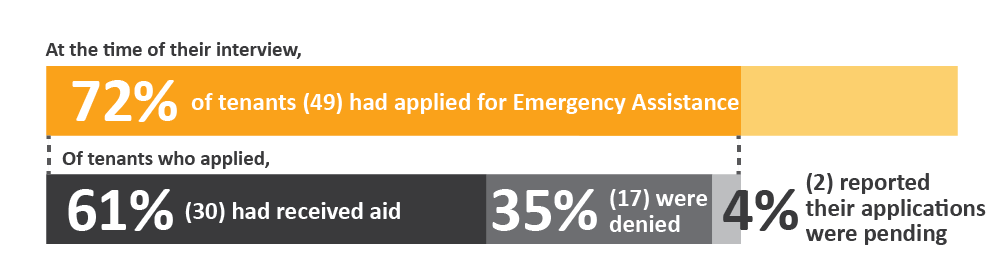

Seventy-two percent (49 tenants) of the 68 tenants we interviewed applied for Hennepin County emergency assistance. Of those, 61% (30) reported receiving aid, while 35% (17) reported being denied. At the time of the interview, two tenants reported that their EA decision was pending.

What Is the Politics of Dehumanization?

Stacy is a 42-year-old multiracial female who experienced three eviction filings in the same property. With a large family, Stacy sought out a space that would accommodate her families’ need but found herself in a home that was not what it was advertised to be. She noted that a once acceptable practice of paying the rent throughout the month was suddenly changed with the first of three eviction filings. From there, she gained knowledge of her legal rights, worked to meet her financial responsibilities, and fought to have all three evictions expunged.

The first eviction filed by the landlord came only 2 months after Stacy and her family moved in. They were late on rent, because her partner was waiting for payment from a painting job. Stacy asked the landlord if he could wait, but he filed an unlawful detainer anyway. Stacy came to court with half the amount owed and agreed to a payment plan for the rest. She honestly did not understand why the landlord filed against her, because she had periodically paid late and sometimes sporadically throughout the month. The landlord had always worked with her.

Stacy sought emergency assistance for rent and utilities, specifically the water bill, because her partner had gotten hurt at his job and they were falling behind on bills. She stated that when seeking EA, all the county wanted to know was if they were going to be able to pay next month's rent and keep up with the utilities. According to Stacy, when applying for EA, a person needed to show proof of an eviction notice for it to be considered an “emergency,” as that indicated the potential for homelessness.

In the meantime, Stacy’s landlord filed second and third evictions for nonpayment, even though the landlord knew that the EA payment was coming. The county paid the landlord before the second court appearance, but at that point, the payment had taken about 45 days and the landlord was not willing to wait.

Although Stacy had planned to move, the cost of the third eviction filing created a new financial burden. She made a payment arrangement and came up with about $3,000 in 2 weeks just to ensure she could move. In the end, EA also paid Stacy’s court fees, because as Stacy stated, “They knew they were so wrong.”

Stacy felt that an unlawful detainer should not be on a person’s record until they are found guilty in court. She said people would rather see someone homeless than give them their day in court, because an unlawful detainer means that many people will end up homeless. “You shouldn’t have to be homeless to be heard.”

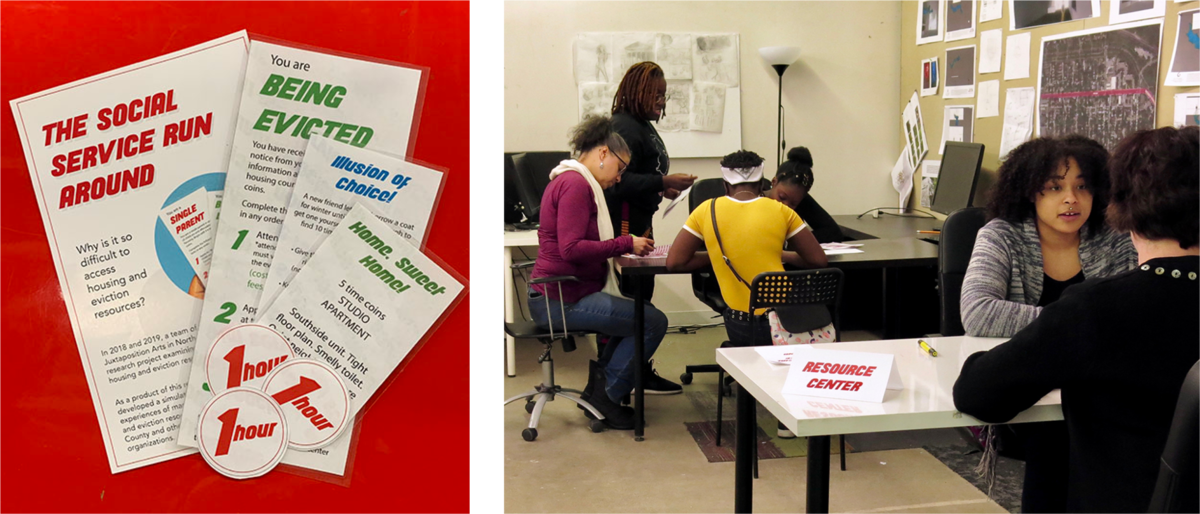

To understand the social services landscape from the perspectives of people providing and connecting residents to housing support, the CURA Evictions research team collaborated with the Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) team at Juxtaposition Arts, an arts education and youth empowerment organization located in North Minneapolis. The youth-led team interviewed eight partners from community-based nonprofits, housing and social service organizations, religious and faith-based organizations, and Hennepin County departments. The interview data were collected and used to create an interactive simulation, The Social Service Runaround, aimed at cultivating a better understanding of the inefficiencies and difficulties inherent in the county’s current social service systems.

The game is structured such that participants are randomly assigned to certain realities, such as “unemployed, seeking housing,” and given a checklist of tasks they must complete, such as “seek unemployment,” before the end of the game. Participants engage in the “runaround” by traveling to and from different social service offices, such as the county and human services office, while waiting in long lines to receive documentation like emergency assistance denial letters needed to obtain other services. Throughout the process, “blessing” and “illusion of choice” cards are given randomly to participants to demonstrate the illusion of choice that people often face when seeking services.

|

The Politics of Dehumanization: Select Illusion of Choice Quotations |

|

Differential Social Services:

|

|

Because [the] majority of the time, someone might not get help, or they'll tell no. They make you feel guilty. Like, every 12 months they put you down. Like, “Oh, well last year we helped you with your water bill. You're still having the same problems. You're not fixing the issue.” I've had staff literally say that to me. Like, “Excuse me, if I'm coming for help with a water bill once a month, or once a year, it shouldn't matter what I'm here for. If I'm here only that one time every 12 months, you shouldn't make me feel bad.” For utilizing what's supposed to be something that's available, as long as you're qualified. But even if you qualify, you still... (Biracial female, 45 years old) |

|

Well, I felt...I'm not a person that bases myself on pride, but it made me feel very worthless going and applying. Because I had a lady that actually told me, “Yeah, we see that you've applied almost every year, and we're not gonna help you anymore.” And I said, “You can't tell me that.” I said, “And I've applied every year, because when something better becomes available, I'll move for the benefit of my children. And if I can save and get new beds, or get new furniture if I ended up having to lose something, I can replace it.” I said, “You guys are here for help.” I said, “I'm sorry. I didn't know it came out of your account, me asking for this help comes out of your personal account.” (Black female, 36 years old) ... But she made me feel real worthless, and I said, you know I work my butt off. I'm not down here trying to scheme, get over. (Black female, 36 years old) |

|

It's always demeaning 'cause they act like it's something that they're giving you out of their pocket and you have to explain why you need it, what brought you to needing it, and if they really, really want to help you. I don't know, I guess you have to be on drugs. I used to be a drug addict, I got 23 years of being cocaine clean. If I was on drugs today I could have basically any service that was provided. You've got to be where you chronically need help so they know that they're going to be getting paid off of you for so long until you at least try to get yourself together or want to get yourself together, and I think that that's sad. I had more services when I was a crackhead than I do as an adult and I'm a homeless adult, they have nothing for me. I got to work everyday, they have nothing for me. I can go and say, “Can you all help me with my deposit?” (Black female, 56 years old) |

|

It took a while. They didn't get back to me right away and of course I was getting nervous. I was starting to pack up my stuff because I thought I was out of here and getting rid of stuff. I had a housekeeper, I had so many pots and pans, I told her she could take a couple of them. I mean I had roasting pans, everything. Nice quality. And she just emptied me out. She took everything. (Native American female, 54 years old) … The interviewer, he seemed to be very interested in what I needed. The lady I met with after that, she was kind of cold. I couldn't understand why she would treat somebody in that manner…I didn't consider myself, but I'm an elder and I was always taught to respect your elders. There was none of that. She treated me like a runaway White person, trashy and I was neither of those things. I was brought up in Coon Rapids. My mom passed herself off as being French, because they didn’t like Natives out there. She used to have to check the yard every day for broken glass. (Native American female, 54 years old) |

|

I just abandoned that pursuit because...but we did go, the first, I think I went twice. The length of the wait was just astronomical. And in today's day and age, I think I sat there, we sat there one time like 2 hours, didn't we? With John Robertson?...And then you know I was doing temp assignments and I had to get to work. And I had already allotted 3 hours to do it. And it already didn't happen within 3 hours and it was just a very frustrating process. (Black male, 51 years old) |

|

I felt that it was degrading, not because I'm above assistance, but that's why I work two jobs. It's because, to me, from what I've seen, the people that don't work, never work or don't try to work. The county give them whatever they want. The ones that do work and get sick—they don't want to help you. The lady even, when I went down there for assistance, she said, "[Informant], you have not been down here since 1990." (Black female, 55 years old) … It took 30 days. It took exactly 30 days for them to deny you. To deny it, and everybody I talked to, because I be talking to other people, and everybody I talked to, they work, they sick, they got assistance from the county and just like me, had one minor child or two minor kids in the house, the county said they made too much. Did the same thing to them. Made them wait 30 whole days to tell them no. (Black female, 55 years old) |

|

Yeah. They told me I didn't make enough income, so that's when I had to add [husband] to the lease for them to pay my half and pay his half. (Black female, 34 years old) … Long, hard, and exhausting...I got denied 10 times. Ten times I had got denied...Ten long, miserable, times people denied me. I cried so hard. I went to a church and the man was going to give me the money to move into the house. And after I got done talking to the man, I felt so relieved, and so free, and I'm like, “You gave me what I needed.” God told me I'm going to be okay. I didn't need the money from him anymore. Yeah, it took me 10 times. I applied 10 times for emergency assistance for the house. I cried, and begged, and pleaded. I'm so tired of being homeless. (Black female, 34 years old) |

|

The process? It was hectic, because when I tried to do it, I got denied. (Black female, 26 years old) ... What they kept telling me was that I needed to have letters saying that I was...I was either getting evicted or am on my way to be evicted...And, by the time the letter came, he was already in the process of doing that, because when I was talking to him, letting him know what I did application for the emergency assistance, and when he found out that it didn't go through, that's when he went and found the papers [eviction notice]. I got the papers, like, a few days later. That the reason why I got denied. (Black female, 26 years old) |

|

Sometimes it was fine. But it all depends on the person you get…Yes. Some of 'em are fine to work with, but others, it's just, you ain't nothin' to them. (Black female, 38 years old) ... Yeah, they give you somethin' to say, you applied...A little form, a regular form they give everybody saying you applied, but it takes 30 days. They can make a decision up to 30 days. But landlords don't wanna wait on that. (Black female, 38 years old) |

|

And yeah, her attitude was real noncommittal, lackadaisical, like she was only there to get a paycheck, let me hurry up and say no to you so I can get you up out of here and I can go home. You know. That was her attitude. And I almost wanted to kind of tell her something, but I was like, ain't no sense in me saying nothing to her, because the application is denied. She got all the power in her hand. You know. (Black female, 55 years old) |

|

The process is a waiting game. It's a lot of paperwork. A lot of unnecessary questions...Where do your money go? Why wasn't you able to pay...What gave the landlord the reason to raise the rent, and questions that wasn't meant for me to answer. (Black female, 44 years old) |

|

Because if you got a job they'll help you. But if you ain't got no kind of income they're not gonna help you. You gotta have some kind of income for them to help you. And I was thinking like, I thought they help people that ain't got income faster they will a person with income. You see what I'm saying? (Black female, 44 years old) |

|

When I went down to see them at the emergency assistance, they told me that I should wait until I got the eviction notice, which was totally new, because I wasn't thinking about it at the time. That meant I would have to go to court, and it was going to automatically still be unlawful detainer registered against me. And then it was a court fee. After I did have to go to court. And there was a court fee. I think it was about $900. (Black male, 66 years old) ... The advice was, instead of just going there and paying rent like I planned, I had most of the rent. I only needed $300. So, instead of them just guaranteeing that money, and letting me pay it right then and there, they instructed me to wait until they posted notification for eviction. (Black male, 66 years old) |

|

Slow, tedious, very invasive. Sometimes it is interesting with them because you can go through emergency assistance and get one worker that'll turn you down. Then when you explain your situation to another worker, she could actually help you or want to help you. Sometimes I felt like as if it was up to them, like they're writing the checks. I know that as a welfare recipient, that's one of the things that you felt like that's what the emergency assistance was for was for assistance to help you so that you won't be homeless. (Black female, 48 years old) |

|

It was hard and kind of discouraging because the lady I spoke with, I don't remember her name now, but she was rude and made me feel like, "You have a job, so why do you need this?" So it was very hard and when I explained to her, "Yeah, I didn't know that I was supposed to get it cut off." "Well, you should know that. That's something you're supposed to know. You're grown," and I'm just like, "Well I didn't." I felt like she was rude to me, and then at first they didn't approve it, and I had to go back again, and the man that I talked to second approved it. So I had to wait about 30 days or 35 days. (Black female, 28 years old) |

|

Yeah, they wanted everything. They wanted my check stubs from my job. They wanted to make sure that I wasn't working, they wanted to make sure that I wasn't hiding no money or none of that. Remind you, I have four kids, and I still had to pay light and gas bills, so I really didn't have no money. My taxes was delayed. My taxes didn't come until July. (Black female, 27 years old) … It took them 3 weeks to even know it was approved. I had gave them everything. I had gave them my tax forms, I had gave them my check stubs, I'm steady calling, I'm steady wondering what's going on until I went up there one day, the last week of me working I had went up there to see if they had processed my case, and luckily I had came up there. The lady was like, "I was just working on it," and she had called my landlord the same day and approved it. (Black female, 27 years old) |

|

Stressful. It was very stressful. We felt like, even just giving up. Why are we even trying, because we already knew that we wouldn't get that in time? (Native American female, 35 years old) … We truly tried, going to the county. What we should have done is went to churches, but we didn't think of that until after the fact. (Native American female, 35 years old) … I did get a letter while we were in shelter, that we were approved for emergency assistance. (Native American female, 35 years old) |

|

It was horrible, it was horrible. I felt, I felt like they didn't wanna help me. I felt like they didn't really care. I felt like they...Okay, so I got in, I went, I applied, and they're like, "Okay, we understand it's your case, it's gonna take a month." I'm like, "Okay, that's fine." (Black male, 29 years old) … It's gonna take a month. And I'm like, "Okay. That's fine. Just let my landlord know this is the first time I applied." They're like, "We're really busy, everyone's coming in. They're applying." I'm like, "Okay, that's fine." So then I'm calling and I'm like, "Do you guys need anything? Do you guys have everything you need?" I'm going in, I'm just double checking, like, "You guys have everything?" And they're like, "Yeah, we have everything. We're just processing it." (Black male, 29 years old) … I'm like, "Okay, that's fine." So then I get a letter after the 30 days is up saying, "We didn't receive your W2's." (Black male, 29 years old) |

|

I wish that the system was more humane for people to have some kind of dignity, somewhere along the way. It'd be okay with asking for help, and not having so many doors shut in your face. And all the hoops you have to jump through, with the county, trying to get assistance. And then find out that you don't get it. Why the hell does that take so long? (Black female, 60 years old) |

|

I don't understand. If I'm making $17, $18 an hour, and tell you that I had a crisis, something happened, and I go ask for help, you tell me, "No." Because I make too much money, or whatever, and I can afford my rent, just need some help. When do you help? (Black male, 47 years old) |

YPAR Social Service Runaround Findings

When the 72% of tenants (49 out of 68) we interviewed described their experiences applying for Hennepin County emergency assistance, also known as the social service runaround in this report, they described it as a slow, tedious, invasive, poorly designed, and culturally insensitive process that requires a denial letter to apply, which often guarantees that the tenant must receive an eviction action on their record. The YPAR team at Juxtaposition Arts interviewed 17 social service navigators to understand the challenges that local resource navigators and the tenants being evicted they serve face as they seek assistance in mitigating the negative effects being evicted from their homes.

The YPAR teams central research questions were:

- What is the landscape of crisis management resources in the Twin Cities metro area?

- Where is the potential to make crisis management resources more accessible?

- What insights do social service navigators have for improvements to the accessibility of these resources?

The YPAR team found three high-level analyses in the data they collected:

- Structural barriers to equality persist. The barriers experienced by social service navigators and those seeking housing and eviction resources are linked and reflective of an imbalance of power and protection between renters and landlords and other forms of structural oppression.

- Trauma-informed assistance is needed. A resource system that integrates eviction prevention and trauma-informed assistance is necessary and one of the first steps to ensuring that people find and keep dignified housing.

- Resource agencies exist in silos. Strengthened connections between agencies and nonprofits offering housing and eviction resources will ease the social service runaround experience for those seeking assistance and make the job easier for resource navigators.

|

Barriers Social Service Navigators Faced |

|

Structural oppression limits access to health, wealth, and housing resources and may also affect an individual’s background. |

|

People can't access the limited affordable housing, because of barriers like backgrounds. They maybe don't have good rental history, that kind of thing. So people are having a hard time. There's not enough affordable housing in general, and people are having a hard time getting into housing. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

Evictions make it even harder to find affordable housing, even if you have enough money. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

I feel that it's really important that when mental health is low, then it makes it even more challenging for you to move forward and to do things in your life. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

Lack of knowledge or access to resources. |

|

People need to understand their power. You are the resource when you are the renter of the property. When you don’t understand this, it limits your power and your ability to go ahead and report [your landlord]. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

You can kind of tell, oh they're young or they really don't know, you know, how to manage. Or they're just confused and want resources, maybe haven't been taught. You know, whatever the situation is. Sometimes it can be someone that's older and they're just set in their ways and they did something and what they also need to be taught some things. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

Retaliatory and exploitative landlords. |

|

One of the most disheartening things that I’ve had happen [in my role] was pursuing a landlord that had retaliatory behavior. And then I had to seek out, number one, how do I prove that, not just based on what I’m saying, I’m seeing. (staff, public agency) |

|

No, it’s not cool. These landlords aren’t living like that, so I don’t expect them to leave people in those conditions. But she was gone before I came, by the time I came back for a re-inspection, her and her three boys were not there anymore. (staff, public agency) |

|

Hoping you don't end up with a landlord who's crap because Minnesota does not have a cap on their rent. So I can have a two-bedroom, I can charge you $1,500 for it and it's absolutely ridiculous. Stability is huge thing. And the thing about it is that if I don't have a roof over my head honestly...I can't deal. There is no way, I'm constantly on sinking sand. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

Recommendations for Change by Social Service Navigators: |

|

Trauma-informed assistance is needed. |

|

By the time they usually get to us, they’ve got a criminal thing, or they’ve got an eviction, versus if somebody when they got that first call was like, “Oh my gosh, this lady is having a mental health breakdown. Let’s avert crisis. Let’s pay her rent. Let’s keep her stable. Let’s not let her enter the system. (staff, faith-based organization) |

|

Intake has noticed that there’s a problem with [a specific] landlord, which might spur an investigation to see if there are issues going on. And then we might help that entire building. Instead of waiting for people to call us, we’ll go out and look for them to see if we can help them. (staff, legal assistance organization) |

|

Revise federal poverty guidelines and Minnesota Family Investment Program (MFIP) grant amounts to reflect today’s housing market. |

|

The federal poverty guidelines haven't really been revised since the seventies. And all government benefits are tied to federal poverty guidelines. So people who are in need can apply for benefits, but benefits are not great enough to pay anything. For a family of one adult and one minor child, your total cash amount that is supposed to be used to pay for rent and buy clothes and medicine or other daily needs is $437. I'm not exactly sure right now what the average amount for a one bedroom or what the average rent for a one bedroom apartment is. A few years ago in the Twin Cities, the average rent for a one bedroom was between $650 and $850 a month. And so $437 isn't really going to even rent you a room in somebody else's house. That's just not enough money. (staff, legal assistance organization) |

|

Increase flexibility for human situations within Hennepin County’s emergency assistance policies. |

|

There was one woman. I said, “Have you ever applied for EA?” She said, “No, but I never will. They treated me so bad. I won’t subject myself to that.” The feedback I’ve gotten, the majority of it is negative. The way they were treated, the way they were talked to. Even suggestions being made of, “Oh, why don’t you sell your stuff? Why do you have a car?” I think that when you’re dealing with a system like that and it’s already broken, then you have people that are talking and dealing with you in that way, it can be traumatizing. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

The county process is frustrating. It takes a lot of time and sometimes [our clients] don’t have that. Eviction is knocking on the door, and the county is taking 7 days to process everything, if you have all your forms. If not, they’re going to send you another letter through the mail asking for another form. And you have to send it in. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

You can only have one crisis a year. (staff, public agency) |

|

Correct the imbalance of power and protections between tenants and landlords, specifically within the eviction process. |

|

There’s a lot of loopholes in the legal system in regards to safeguarding our renters. You can contact 3-1-1 to have a housing inspector come out. The thing about the way that [is] set up is that the landlord does not have the right to evict you after you’ve contacted 3-1-1, but that’s only 90 days. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

Find ways to better support agency/nonprofit staff who directly engage with clients and the housing resource system. |

|

You see a lot of things, like domestic violence, which really triggers people. Or you may see a child that gets removed from their home into child protection, and what does that do to somebody? (staff, faith-based organization) |

|

We have to try to account for self-care and burnout for folks, because working with this population can lead to a level of tiredness and disparity. The work doesn’t always have good outcomes. (staff, faith-based organization) |

|

Resources Social Service Navigators Wish They Could Give Their Clients |

|

|

Transportation is a huge thing. So being able to have programs that actually give out cars or either have some type of 0% loan for people who wanted to purchase a car. So, there's so many people who operate kind of like in that low-middle-class bracket, income bracket, and they're the ones who seem to fall through the cracks so many times. So they don't, they make too much to get assistance, and then they don't make enough to be able to take care of themselves. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

|

|

More resources that get targeted towards small landlords of what—you know, when they send the eviction letter or the letter of nonpayment, what needs to go on the back of that letter? About how to access a county or how to access emergency, what steps to go through. How do we get more out to, to—because I make the assumption that 50% of landlords don’t want to have a housing turn over. Some it’s just their business model. (staff, nonprofit organization) |

The YPAR team found overlapping themes in the larger evictions report findings (see Landlord Findings and Tenant Findings). However, the team highlighted three different problem areas that were not explored in the larger report. First, that the federal poverty guidelines have not been updated since the 1970s, which informs the monthly dollar amount that families receive from the county if they qualify for government social services. Navigators determined this to be financially constraining in the current housing market. Second, Hennepin County has control over its own policies and has exercised that power to make situational changes, sometimes giving people access to funds beyond their once-a-year allotment, but their current policies do not match their clients’ urgent needs. Third, many social service navigators work within organizations that are unable to pay their staff a livable wage, forcing many navigators to seek the same resources that they are assisting their clients in securing.

Discrimination Against Single People

Eleanor is a 46-year-old single Black woman who works full-time and is still living in the same home where she experienced three unlawful detainers. Her landlord bought the foreclosed home in February of 2017 and rented it to her in March, making no repairs. While living in the home, Eleanor experienced a number of serious issues, including a broken water heater, a stove that never worked, a water-damaged ceiling, a flooded basement, which led to mildew, and a refrigerator that had to be replaced twice. In June 2017, Eleanor wrote a letter documenting all the items that needed to be repaired and sent it to her landlord. Almost immediately, the landlord filed the first eviction. After the eviction filing and as a result of the unmade repairs, Eleanor began to withhold her rent.

After Eleanor sent the letter to her landlord, she reached out to City Inspections and a number of code orders were issued. However, as soon as the inspector spoke with the landlord, Eleanor felt she [the inspector] was on “his side.”Although she requested them, she never received code orders. Finally, Eleanor called the inspector’s supervisor to report that the work had never been addressed and she found that the city order was marked as resolved even though no repairs were actually made.

The first time Eleanor and her landlord appeared in court, the case was dismissed and expunged because the landlord did not have a rental license. Although she should have utilized escrow, Eleanor did not know the system, so she simply kept her money orders each month. The next month, her landlord filed another unlawful detainer for nonpayment due to Eleanor withholding the rent until repairs were made. They returned to court.

While at court, Eleanor consulted a Legal Aid attorney who suggested applying for an expungement, a process Eleanor would not have known about without the attorney telling her. Although she tried to mediate at the insistence of the court, the conversations were not productive. Eleanor’s landlord would say “nasty things” to her and would not respond to the list of repairs that needed to be made.

During this process, Eleanor had gone down to the Hennepin County emergency assistance office to apply. The worker asked for her income and denied her on the spot. Eleanor left EA without a denial letter to take to other service providers. Eleanor went further to state that, “It's kind of hard...As a single person...you really can't get much assistance because they're looking at the fact you don't have dependents.”

Eleanor has now experienced a third eviction. She is disputing the eviction, still waiting for repairs to be made and headed to trial. She attempted to apply for new housing during this time, with no luck. Eleanor is now stuck in the place where she has received three unlawful detainers.

An understudied reality of the city and county’s scope of social services is their limited support for single adults. Currently, the Emergency General Assistance (EGA) program is the only source of support for single adults in a social service landscape where having dependents guarantees you immediate placement into county shelters and access to housing placement support services. All tenants interviewed who were single adults expressed feeling discriminated against for not having dependents, because they did not receive empathy for their state of financial duress since it was assumed they would be better off since they were only responsible for themselves. This premise does not account for the fact that rents and the general cost of living have increased while wages have stayed stagnant, forcing single people to struggle to feed, cloth, and house themselves. Single people seeking resources are then made to feel ashamed for their presumed inability to care for themselves.

Yeah. Honestly I think...I don't know...I can't...I can only speak for me. I feel like it's hard being a single adult with no kids. And then the thing is when you have too many kids, you become a stereotype. You have no kids, well then it's like what do you need help with; you don't have any kids. You know what I mean? So it's kinda like, don't have any kids because you don't wanna become that...you know, I got four kids and I'm at the county. But if you don't have kids, it's just like...I feel bad for asking; like why are you asking them for help. You shouldn't be here, because you don't have any kids, you know? And what they don't understand is, with or without kids, they're still paid the same amount at work. They don't base your pay off of how many kids you have. (Black female, 30 years old)

It's kind of hard. Sometimes, just being a single person, you know, as of right now, I mean it's like you, things count against you whether you're single or if you have kids. As a single person, you really can't get a lot of, if you need some assistance, you really can't get much assistance because they're looking at the fact you don't have dependents.(Black female, 46 years old)

The “Dollar Over” Club

Ann is a 50-year-old Black mother of a teenage son. She was working full-time for Minneapolis Public Schools and had secured a place in a new high-density housing development in North Minneapolis when she experienced significant loss of family members who were close to her. Ann feels that this loss and her resulting depression is what led to her eviction. Ann shut down and was completely checked out at work. She was eventually let go from her job. Once Ann’s unemployment had run out, she could no longer pay rent at all.

Although the property manager tried to help her through the process, eventually Ann was evicted from the home. At the time that Ann received the eviction notice, she had already hit rock bottom and was seeing a therapist at HCMC regularly. At this point, Ann applied for EA but was denied. The process took up to 30 days, by which time she knew she would be evicted and on the street. At the time she applied, EA required Ann to have an eviction letter, which didn’t make sense to her because she was trying to prevent an eviction.

From Ann’s perspective, the process was not humane and there were too many hoops to jump through with the county.

I wish that the system was more humane for people to have some kind of dignity, somewhere along the way...And all the hoops you have to jump through with the county, trying to get assistance. And then find out that you don't get it. Why the hell does that take so long?...They said that we have up to 30 days to respond. First of all, I'm like, “Hell, we're getting evicted in a few days.” It's like you have to have an eviction letter for them to even bother seeing you. It wasn't like, no, pre-eviction. Hell, I know I don't have the money, so I'm coming to you now to keep from being homeless in the first dog-gone place…Then, okay, now that I see you, you want me to bring proof that I got an eviction letter, okay. Now I got an eviction letter. [EA then asks] “Well, where's your money at? How much money do you have in the bank?” I need that to eat. So if I don't have no place to stay, I still need to eat something. I don't have a place to stay, I still need transportation to get back and forth.

Ann was a member of the “dollar over” club, meaning that her income was slightly more than the eligible amount so she was unable to qualify.

While Ann was going back and forth trying to locate and submit all of the required documentation, she went into the EA office to check the status of her application. She learned that her paperwork had not yet been entered into the system. She was very upset. She met some real genuine people and then others who made her feel like she was taking money out of their pockets.

Ann was eventually evicted from her home and is currently homeless and staying with a friend. Going forward, she feels like the most significant barriers to secure housing including racial discrimination is the unlawful detainer on her record and a challenging rental history.

Ann, like many other tenants in the dollar over club, were mothers working full-time to make what our market-driven nation has determined to be a livable wage, despite the fact that the current minimum wage does not incrementally increase with cost of living. However, these tenants are living paycheck to paycheck, with many paying market-rate rent. Knowingly living one crisis away from becoming homeless, despite having full-time employment, Ann found a series of deaths in her family forced her into a deep depression that left her unable to fulfill her employment responsibilities. She applied for emergency assistance when she received her eviction notice, and it was determined that she made slightly too much money to qualify and that any savings she had left should be applied to the emergency itself. Ann was quite frustrated, as she was using her small amount of savings to feed and clothe herself and her son while couch surfing. Similarly, other tenants in the dollar over club stated that in order to receive assistance they needed to not be working at all or very little.

The dollar over club reaffirms the YPAR team’s findings of a deep need to reevaluate the federal poverty guidelines and MFIP grant amounts, which severely impact the ability of those most in need from receiving resources. In today’s housing market, those we refer to as members of the dollar over club are those who do not typically seek county resources, but severe familial crisis or job loss forces them to seek support to get themselves and their families back on their feet. These are often women working in the low- to moderate-wage sector who have lived mostly in stable housing with a livable wage, but without spousal income.

Yeah I got turned out, but I just didn't go back after I got turned down. It was always I'm a dollar over, you know, they got this you have to be within every, a dollar range of something. (Black female, 60 years old)

Seriously. Seriously. That's how it feels. It has to be just that dollar because I'm really in need and it seems like you're the candidate because you work, you're in need at the time, and you know once you get that help you can bounce back. However, you're denied and you're approved when you have nothing on the table. So, it's just very very frustrating. It just feels like the help is there but not really and you're like, "Who is it helping?" (Black female, 30 years old)

Conclusions and Implications

When assessing how and why evictions take place from the perspective of tenants and social service navigators as they reflect on the impact that the social service system has on their lives as they are navigating an eviction, the following major themes emerged from our interviews and that of the YPAR team at Juxtaposition Arts:

- Clients feel intense dehumanization and despair when attempting to access (successfully or not) various parts of the social services network in Hennepin County. There are short- and long-term mental health implications related to the stigma of unlawful detainers and homelessness.

- Several interviewees saw how potential tenants seeking housing with UDs on their records would have their applications denied and actively worked against this trend, interacting with applicants in good faith and not using UDs as an automatic disqualifier for housing. They named UD reform via expungement options as one route to destigmatizing a pressing problem affecting tenants of color in Minneapolis.

- The education of clients about the social services system and their rights as tenants is a vehicle for personal and community empowerment.

- There is a need for humane and culturally appropriate services and interactions between tenants and their families with landlords, property managers, and county social services employees.

- Many interviewed named retaliatory landlords and landlords with eviction rates higher than 50% as a particular concern because of the trauma involved in repeated negative interactions and turnover of affordable housing to investment firms that do not retain affordable units.

- A moral reorientation of social services is a necessary first step to ensure housing stability for Minneapolis residents.

- Numerous interviewees discussed how their social services organizations placed relationship-building with tenants as a major component of their work to ensure tenants’ stability and comfort, with much success in regard to keeping evictions and tenant turnover low.

- The federal poverty guidelines have not been updated since the 1970s, which informs the monthly dollar amount that families receive from the county if they qualify for government social services and that navigators determined to be financially constraining in the current housing market.

- Tenants in the dollar over club stated that in order to receive assistance from the county they needed to not be working at all or very little.

- Hennepin County has control over its own policies and has exercised that power to make situational changes, sometimes giving people access to funds beyond their once-a-year allotment, but their current policies do not match the clients’ urgent needs.

- Social service navigators work within organizations that are unable to pay their staff a livable wage, forcing many navigators to seek the same resources that they are assisting their clients in securing.

- All tenants interviewed who were single adults expressed feeling discriminated against for not having dependents, because they do not receive any empathy for their state of financial duress since it is assumed they are better off since they were only responsible for themselves.

When CURA’s Evictions research team interviewed tenants and the YPAR team interviewed social service navigators, we collectively found that the county’s social service processes leave its clients feeling less than human and retraumatized. The “runaround” is simply a term that tenants themselves used to describe the slow, tedious, invasive, and culturally insensitive process they felt forced to navigate to receive county resources. Many times this was due to smaller support agencies’ requirement to receive a denial letter from the county to access other partner funds. Many tenants recalled begging and pleading with workers and sometimes bursting into tears as they saw no other way to remedy their crisis. We found that the voices of single people and those tenants in the dollar over club often go unheard, because they do not have dependents and/or it is assumed that they should be able to take care of themselves. For members of the dollar over club, they made slightly over the federal poverty guidelines and were immediately denied, making them feel they could have received help in their time of need only if they had not been fully independent prior to their crisis.

However, the YPAR team’s interviewers with social service navigators produced a series of recommendations from the navigators themselves. The navigators called for a reevaluation of the federal poverty guidelines, a reimagining of county emergency assistance policies to meet the urgent needs of clients becoming more nimble, strengthening connections and information sharing between agencies and nonprofits offering housing and eviction resources, and providing a livable wage to social service navigators, because they are forced to seek the same resources that they are helping their clients to secure.

The Illusion of Choice report aims to explore how and why evictions take place from the perspective of those most impacted, yet we did not intentionally set out to include the social service system and the role of the state. However, very quickly into the project, it became apparent that the state (e.g., social services) plays a significant role in aiding or disrupting tenant and landlord success. According to tenants and paid social service navigators, the county social service system falls short of its commitment to its clients and their families. In fact, the county is retraumatizing not only their clients but also is leaving its social service navigators without the resources they need to be successful in their work.

Read the next part: Research in Action: The Value and Impact of Actionable Research