The production of community-centered public policy and programmatic solutions is predicated on our ability as community-engaged action researchers to allow the voices of those most impacted to guide and identify the places where change is needed the most. Then we aim to utilize the relationships built across institutional spheres of influence to bring those marginal voices to local decision-making bodies.

To do this, first, we must understand what policy prescriptions are being used nationally and locally. Second, we must pay close attention to the individuals and institutions that have had the most impact on those we interviewed and their ability to maintain safe, affordable quality housing. We do this to assess whether or not local policy prescriptions are actually addressing the needs of those most impacted. Third, we focus on the gap between what policy and programmatic interventions local power brokers support publicly and what issues arose from interviews with those most impacted. These gaps are under-analyzed sites of policy change. We do this in an effort to utilize our data as an advocacy and policy-framing tool that helps to draw our attention to under-analyzed areas of intervention that often only those experiencing the realities of housing instability would be able to readily identify. In short, we treat our research participants as the experts on their own realities.

From the National to the Local: Common Policy Frames and Divergent Approaches

Across the United States, tenant organizing highlights a number of serious housing concerns, including unsafe and unhealthy living conditions, unresponsive landlords, dramatic rent increases, and evictions (Ortiz, 2018). Three of the major national policy imperatives highlighted by tenants, organizers, and housing advocates across the country are right to counsel, universal rent control, and just-cause eviction (also termed “good-cause” eviction).

Right to Counsel

Right to counsel is “the commitment to make legal services available to all tenants facing eviction in housing court and public housing authority termination of tenancy proceedings” (New York City Human Resources Administration, 2018). Tenant activists and supporters argue that tenants are often in financially and socially precarious situations when facing eviction proceedings with landlords and public agencies. Tenants should have the right to counsel to mitigate some of the initial power imbalance. New York City recently passed right to counsel legislation when organizers fighting for right to counsel succeeded. In August 2017, Mayor Bill de Blasio signed Intro 214-b into law, officially guaranteeing New York City tenants this right, which resulted in 33,000 households receiving free legal representation, advice, or assistance through the city’s Office of Civil Justice. Several other jurisdictions have implemented or are considering some degree of right to counsel for evictions, based on the income of the tenant or category of housing involved (e.g., Washington, DC, San Francisco, Philadelphia). During the 2019 Minnesota legislative session, State Senator Kari Dziedzic introduced a bill that would provide court-appointed counsel for certain tenants facing eviction from public housing based on allegations they had breached the lease (SF 1785).

Universal Rent Control

Rent control is a set of regulations on yearly rent increases and the terms of eviction actions, and policies sometimes can also restrict how much a landlord can charge for rent, based on tenants’ eviction history (Tenants Together, 2019). Rent control was originally a federal price control implemented during World War II, but now it is typically a municipal, county, or state regulation that leads to serious challenges for rent control advocates in states with state-level laws regulating rent control on the municipal or county level. While opposers cite studies tying rent control to the reduction in the quantity and quality of available housing, proponents hold that it provides a necessary economic stop-gap for neighborhoods experiencing gentrification due to massive reinvestment in real estate and infrastructure after decades of targeted disinvestment (Stein, 2019). While California, New York, New Jersey, and Maryland have rent control in certain municipalities, Oregon is the only state with universal rent control. This came about after two decades of work by tenant groups, which led to the passage of Senate Bill 608, a state law restricting “annual rent increases to 7 percent” and banning no-cause evictions (Walker, 2019).

Just- or Good-Cause Evictions

In most cases, a landlord in Minnesota may legally terminate a lease at its expiration date (or at the end of the month for a month-to-month tenancy) as long as they have given proper notice based on the lease terms and the law. The landlord does not need to have a specific reason in most cases not to renew a lease. A just-cause eviction policy would require that even when a lease expires, a landlord would need a specific, legally valid reason to not renew or continue the lease with the current tenant. Cities or states with these standards allow eviction or nonrenewal of a lease only if the tenant has violated the lease terms, failed to pay rent, or some other specific reason permitted by the law. Just-cause laws can be instituted at the municipal, county, or state levels; vary across the country; and are often included in rent control laws to specify the terms of eviction for residents in rent-controlled units. Given the constraints on landlords’ ability to serve non-renewal notices at the end of a tenant’s lease term, just-cause laws receive pushback from associated parties. Additionally, tenants are often left with only the limited protections described in their leases in municipalities and states without just-cause laws. Actions for just-cause are front and center for urban tenants facing rising economic pressures from stagnant wages and gentrification. Recent activism by the Philadelphia Tenants Union and other housing activists led to the unanimous passage of Good Cause by all 17 members of the Philadelphia City Council—later signed into law by the mayor in January 2019—demonstrating the need to ensure tenants are treated fairly in relationships with private landlords (Merriman, 2019).

Approaches to Policy and Program Change in the Twin Cities

Policymakers and tenant advocates in Minneapolis and Saint Paul have pursued similar interventions and found varying levels of success in shifting local policies and practices. Former Minnesota Congressman (now Minnesota Attorney General) Keith Ellison introduced federal legislation on the issue titled HR 1146, the Equal Opportunity for Residential Representation Act, which stipulated the creation of a pilot program providing grants to housing-related organizations, including those that provide civil legal services to families facing eviction, landlord/tenant disputes, or fair housing discrimination. While this legislation did not make it out of committee, local organizations continue to work on right to counsel legislation.

Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid and the Volunteer Lawyers Network “Right to Counsel”

Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid and the Volunteer Lawyers Network are two such organizations researching and advocating on the issue. In their 2018 project titled Legal Representation in Evictions, they sought to determine whether legal representation for tenants in the Fourth Judicial District Housing Court provides tenants meaningful benefits in housing stability. The organizations found that fully represented tenants won or settled their cases in 96% of these cases, while those without any legal services won or settled only 62% of these cases (Grundman and Kruger, 2018). Moreover, in cases where tenants agreed to move, fully represented tenants received twice as much time to do so and were drastically less likely to have an eviction record after this agreement if they were represented by a lawyer. These findings support Minnesota legislative bills on right to counsel, 14-day pre-eviction notices, and eviction expungement reform.

HOMELine “Right to Cure”

HOMELine, a Minnesota-based nonprofit tenant advocacy organization, advocates for tenants’ rights to receive adequate notice of a potential eviction action and for limiting the effects that past evictions have on future housing options (HOMELine, 2019). A “right to cure” pre-eviction policy would mandate a 14-day notice, allowing the tenant the opportunity to get current on rent or remedy a breach of lease before the landlord can file an eviction action. Forty-three states require some kind of notice to tenants before a court eviction is filed. Minnesota is one of the seven that does not. Many tenants interviewed in The Illusion of Choice report expressed frustration with the small window of time provided once an eviction notice is filed, because it does not align with the Hennepin County emergency financial assistance process. Moreover, eviction actions mark tenants’ rental housing records long term, partly due to the situation just described but also because eviction actions remain on a tenant’s record and publicly accessible for decades—information that most if not all the tenants interviewed were completely unaware of. To ensure tenants can secure housing in the future, eviction expungement reform plays an important role in the legislative agenda of HOMELine and other tenant advocacy organizations, particularly giving tenants the right to due process before an eviction is placed on their record and limiting the amount of years that a UD stays on a tenant’s record.

InquilinXs UnidXs por Justicia’s “Tenant’s Bill of Rights”

Inquilinxs Unidxs por Justicia (United Renters for Power, or “IX”), a Minneapolis tenant power organization, seeks to challenge the present political economy of commodified housing. The group was initially organized in 2015 to acquire pro bono legal representation to sue a negligent landlord. Today, IX members utilize a tenant powerbuilding model to support their education and development as they fight for systemic changes in housing while dispelling myths about the lack of roots that renters have in a community. Housing cooperatives, tenant unions, and rent control are imperatives for IX members, who also cite the necessity for lawmakers to sign a “tenants’ bill of rights which would provide tenants additional legal mechanisms to more evenly negotiate with their landlord over applications, repairs, or displacement” with the engagement and support of Minneapolis tenants (IX, 2018). IX’s focus on building tenant power highlights important contradictions in the US housing system: policies like rent control empower tenants and change the terms of their housing situation. In the current system that commodifies housing, real estate interests take community members’ spaces of labor and convert them into spaces of profit (Stein, 2019). Thus, supporting policies and strategies that aim to separate the profit relation in housing are important components of building tenant power and control for IX and partners.

CommonBond Resident Support

In addition to these national and local policy proposals and their supportive advocacy efforts, local housing and social services professionals are making important programmatic changes to address the evictions crisis. CommonBond Communities (also known as CommonBond), a large nonprofit affordable housing developer delivering services in the Midwest United States, focuses on “supporting residents of all ages to achieve long-term stability and independence” through on-site programs and services and organizational partnerships, and community-building and engagement; some of these activities have an expressed goal of reducing the risk of eviction for residents housed in CommonBond properties (CommonBond Communities, 2018). Performing a social return on investment (SROI) analysis of CommonBond’s eviction prevention program (EPP) activities revealed a return of “$4 in social benefits generated for every $1 invested by CommonBond.”

Hennepin County Pre-Eviction Pilot

Similarly, a Pre-Eviction Pilot (PEP) carried out by Hennepin County, the McKnight Foundation, and the Pohlad Family Foundation trialed a program in North Minneapolis to reduce evictions. This project, which took place from January to November 2018 at NorthPoint Health and Wellness, focused on preventing eviction filings among residents who experienced hardship paying rent, bringing together financial, social, and legal services to mitigate the potential of an eviction action regardless of tenant income. After examining pilot data, the researchers concluded that most PEP participants remained housed, did not experience an eviction filing, accessed helpful legal and social services, and did not need to utilize an emergency shelter. The findings demonstrated methods that governments, research centers, and tenant advocacy organizations can promote to reduce and ultimately eliminate evictions and mitigate resulting harm to individuals, families, and communities.

Ramsey County Emergency Assistance Restructure

Ramsey County piloted an emergency assistance service restructuring program titled “Continuous Improvement, Immediate Action” from 2013 to 2014. The design-oriented practices of the Kaizen method utilized by Ramsey County fostered significant changes in emergency assistance design, implementation, and evaluation, indicating the strengths of a collaborative process of policy revision to improve service delivery. “With an average wait of less than five days from initial application, county assistance is better aligned with state mandates for eviction proceedings, increasing the likelihood that residents will be able to avoid housing court” (University of Minnesota College of Design, 2018).

CURA’s Policy Recommendation Process: Policy Interventions from the Ground Up

It is critical that we pay close attention to work already being done both nationally and locally to mitigate the negative impacts of evictions, while also acknowledging that these reform efforts are a larger part of a complicated system that does not always ask those most impacted what they want or need. Unfortunately, our nation's history of paternalism often prevents us from seeing low-income people of color as the experts on their own realities. To resist the common paternalistic approach that public policy development often takes, CURA’s Evictions research team engaged in a three-part process to guide the creation of the CURA Evictions Policy Recommendations. This process included:

- a review of the interview data to analyze policy recommendations that arose from stories shared by tenants, property managers, landlords;

- an analysis of current policy proposals being made by local policymakers in Minnesota regarding evictions at the city, county, and state levels;

- an evaluation of tenant and landlord perspectives on those current policy proposals to assess whether or not those most impacted believe they are the recommendations that the city, county, and state should pursue.

A Review of Interview Data

The research team reviewed the interview data from the 32 landlord and 68 tenants interviewed, while looking for themes and suggestions for public policy and programmatic interventions that aimed to ensure the success of the tenant and landlord relationship. Although participants were not asked for their policy recommendations outright, several tenants and landlords provided examples of changes to the eviction process that would provide relief for both. For example, one tenant noted:

Giving somebody seven days to move [after eviction hearing], that's really not enough time for, I mean just think. If I was still working in the same jobs I was working before, I wouldn't be able to pull that off. You would have to get a moving truck, get everything packed up, and if you work, you've got to go between your work and trying to get everything done and moved out, and with the process of that they're using now to find housing, there's no way. (Black female, 46 years old)

Another example came from a landlord who discussed some of the challenges from his experience with the county’s emergency assistance programs. As noted previously, the emergency assistance process was a recurring topic of frustration for both landlords and tenants. One landlord noted:

Our experience is we sometimes see people get denied and we're like, “You know, if you just would have helped them, like maybe with two months’ rent, they could have gotten back on their feet.” Now they're spending all of their extra time with children, and all their other things in their life, when they just needed maybe one more month, and it would have been a greater success. But the cut off is just so fast and hard. And I get it, right? But this person who maybe didn't quite have their new job yet. They were in between jobs. Emergency assistance won't help unless they can prove they can pay the next month's rent. What if we loosened that for 45 days, and then the resident gets help, and then it's a one-time help versus an escalating...It's expensive to move for the resident. Not to mention what it does to the, if they have children, and the disruption. (White female, 46 years old, property manager for a for-profit organization)

Examining tenant and landlord interview responses in the context of their eviction experiences allows for an inductive and organic assessment of both short-term and long-term priorities of each participant, which also assisted us in identifying places where policy and programmatic reform was necessary.

An Analysis of Current Policy Proposals

To engage with local policymakers, the CURA Evictions research team invited Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid the offices of council member Jeremiah Ellison and state senator Bobby Joe Champion to meet with the CURA Evictions Advisory Council to discuss current and future policy and program proposals aimed at mitigating the impact of evictions at each level of the government. In total, the Advisory Council outlined 16 different policy recommendations based on the information provided by these representatives, along with information from ongoing initiatives such as the city of Minneapolis Conduct on Premises work group. These policy recommendations included proposals such as limits on background checks, shortening the emergency assistance and emergency general assistance decision timelines, changing conduct on premise regulations, and ensuring legal representation in Housing Court. The CURA Evictions research team compiled and examined all of these recommendations.

An Evaluation of Tenant and Landlord Perspectives on Current Policy Proposals

In a community-engaged action project, policy recommendations cannot end with the traditional experts. They must be produced, vetted, and enhanced by the community members who stand to be impacted the most by the implementation of the recommendations. To gauge tenant and landlord perspectives on the current policy proposals, the CURA Evictions research team compiled 16 policy proposals, outlined by state and local officials, into an electronic policy survey and sent it to all 100 research participants (68 tenants and 32 landlords). A CURA Evictions research team member attempted to contact each participant a minimum of three times, either by phone, email, or text message. For each policy or program proposal, the survey prompted participants to choose between three responses: “strongly agree,” “neutral,” or “strongly disagree.” Additionally, the survey included open-ended text boxes to allow survey participants the option to comment or elaborate on their responses. At the end of the survey participants could offer their own general insights and recommendations for eviction policy.

In total, 26 (38%) tenants and 16 (50%) landlords responded to the survey. It is important to note that within the 4 months between the end of interviews and the online policy survey, the contact information for approximately 12 (18%) of all tenant participants was invalid. Several other tenants’ phone numbers were out of service, and although a team member reached out via email, these requests for input garnered no response. This is a serious challenge, research limitation, and characteristic emblematic of working with highly mobile populations; however, it does not deem the responses received irrelevant. Rather, the integration of feedback from tenants and landlords who experience and participate in eviction actions in Hennepin County plays a critical role in our broader policy recommendations. The lack of a complete set of participant responses should not dismiss the saliency and gravity of the resulting recommendations. The research team used this data to inform, reinforce, and critique the policy recommendations outlined next.

Utilizing our three-part process, the research team identified three major policy recommendations that can support efforts to prevent eviction action filings and mitigate their consequences.

CURA Policy Recommendations

Policy Recommendation #1: Extending the Length of the Evictions Process

If the notice is for eviction, and the landlord does not have a “just cause” for the eviction, the landlord should give the tenant a 30-day notice from the date the rent is paid on, to move. Nothing less. (Black female, 55 years old)

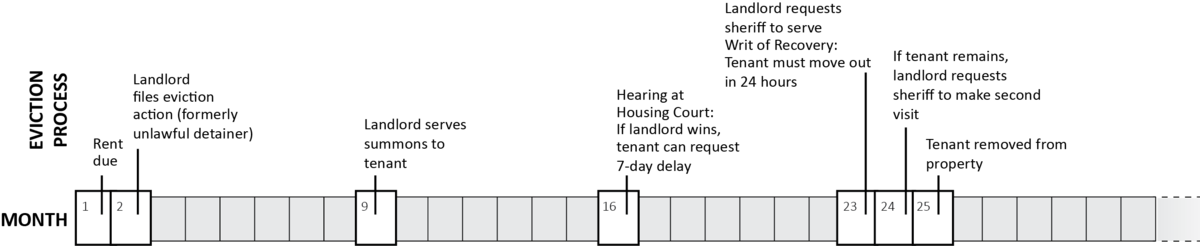

We recommend extending the length of the eviction process. Minnesota has one of the fastest court eviction processes in the country. Under current law, a landlord can file an eviction the first day rent is overdue. An initial hearing is held between 7 and 14 days after the landlord files the case (Minn. Stat. § 504B.321). If the case is not resolved at that hearing, the tenant faces a full trial, which the court schedules for a maximum of 6 days out (Minn. Stat. § 504B.341). According to the Minneapolis Innovation Team’s report, on average, eviction filings are closed in 14 days, with over 90% closed within 30 days. The rapid nature of the process leaves minimal time for tenants, Legal Aid, and emergency assistance to garner the resources necessary to resolve or mitigate the consequences of an eviction action.

A rapid evictions process is particularly concerning in tight rental markets. Although the demand for rental properties is high, which benefits most landlords, the supply of housing is low, which places renters in a precarious position of accessing and maintaining a home. CURA aims to center the tenant in this policy recommendation, as preventing and mitigating the impact of evictions may also prevent further economic, social, and psychological burdens.

Currently, Hennepin County hosts one of the fastest eviction timelines in the country, according to Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid. More time should be allotted to help individuals and families transition through a difficult and arduous time, enhancing their ability to seek additional resources to prevent displacement. HOMELine, a partner in The Illusion of Choice project, has outlined a sample evictions timeline:

Evictions and Emergency Assistance Processes

Community Voice and Response

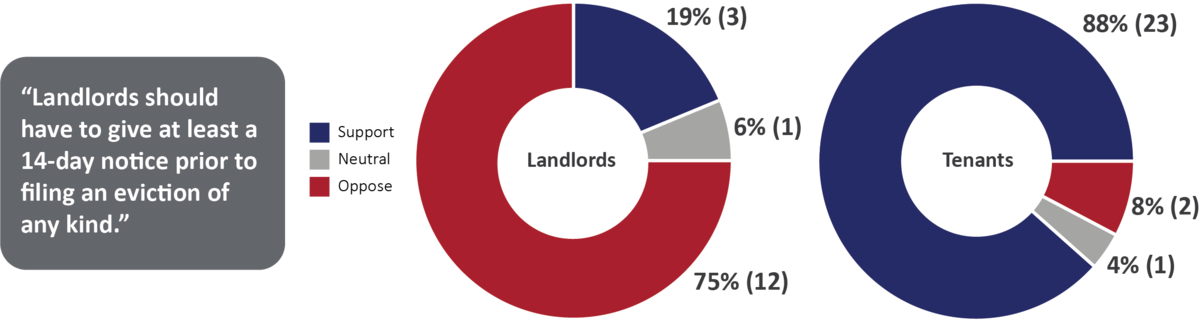

Community advocates and policymakers have aimed to lengthen the eviction process in an effort to create a process that is more responsive to vulnerable tenants. Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid presented its recommendation of extending the eviction process to the CURA Evictions Research Advisory Council. One way to do this would be to require landlords to give tenants a 14-day notice prior to filing an eviction of any kind (except expedited action). Additionally, Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid proposes additions to the statute that all filings would require more detail about conduct on premise violations and the exact financial information in question for nonpayment of lease filings. When asked, tenant and landlords had different responses in terms of levels of support for this policy proposal:

Clearly, there is a discrepancy in the support for this proposal between landlords and tenants. As one landlord noted, “The eviction process is already unacceptably slow and expensive. This addresses and rectifies none of the underlying problems.”

Another landlord explained:

A property costs a great deal of money to maintain every day, and adding 14 days onto the possession by a potentially non-paying party can unfairly cost an owner money that they should not have to lose. A lease outlines reasons for possible eviction, and tenants should be aware that they can potentially be evicted for not paying rent or violating terms of their lease. (White female, 35 years old, individual property owner and manager)

On the other hand, tenants were in high support of this proposal. One tenant noted that this “would give tenant[s] time to get money together if need be.” CURA recognizes the time and expense of eviction actions for both landlords and tenants. Although, it is important to note that landlords and tenants throughout this project cited that often landlords who file an eviction action pass on the filing cost to the tenant. This cost for Hennepin County is $297. To build housing stability, particularly in high eviction action areas such as North Minneapolis, the state must allow time for tenants to garner the resources to mitigate the impact of eviction actions.

Policy Recommendation #2: A Humane and Timely Approach to Emergency Assistance

I wish that the system was more humane for people to have some kind of dignity, somewhere along the way. It'd be okay with asking for help, and not having so many doors shut in your face. And all the hoops you have to jump through, with the county, trying to get assistance. And then find out that you don't get it. Why the hell does that take so long? (Black female, 50 years old)

Yeah, they [emergency assistance] give you somethin' to say, you applied...A little form, a regular form they give everybody saying you applied, but it takes 30 days. They can make a decision up to 30 days. But landlords don't wanna wait on that. (Black female, 38 years old)

We recommend a revisioning of the social services model utilized in the emergency assistance (EA) and emergency general assistance (EGA) programs. It is imperative that the revision center on culturally relevant service, as well as a reduction of time spent processing EA/EGA requests aligned with the Housing Court eviction process. Ensuring that the EA/EGA system centers the needs of each individual and/or family is vital to this vision. Additionally, due to the rapid nature of the eviction action process, the timeline of EA/EGA application and appeal response needs to be shortened. We recommend an open and transparent community-engaged process for collecting feedback from those most impacted by the EA/EGA program that includes diverse partner organizations and advocates.

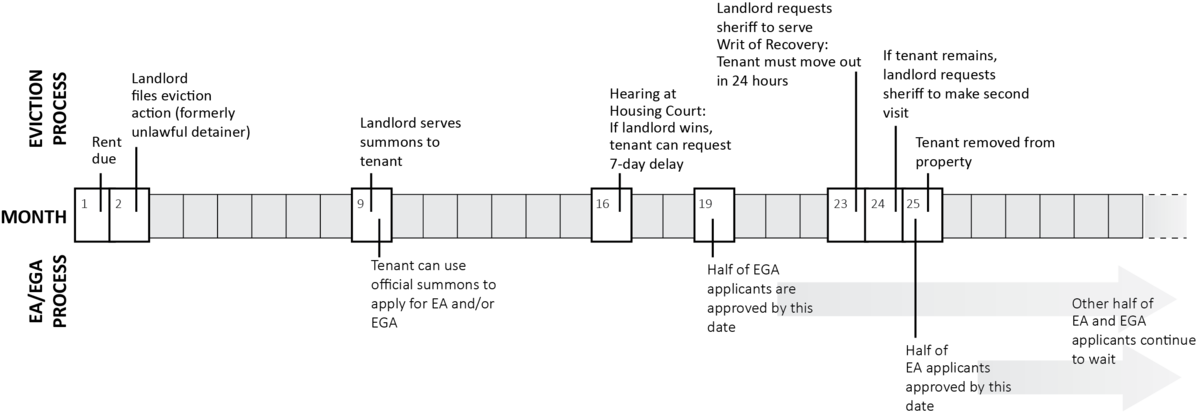

EA/EGA programs serve roughly 5,400 and 3,600 households, respectively, each year, helping those behind on rent or struggling to pay utility bills. Hennepin County also provides case management to 30,000 people each year, and case managers can be a strong partner in maintaining housing for clients. The speed of Housing Court stands in contrast to the speed with which Hennepin County responds to housing emergencies brought by clients. For families served by the EA process, half are approved in 16 days and half of EGA cases are approved within 10 days. However, more cases are denied than approved, and those have median denial times of 20 days and 31 days, respectively. Housing Court, on the other hand, has mandated timelines of “first appearance” in court within as little as 7 days after service of notice to the tenant. If the case is not resolved at first appearance and the tenant convinces the court that a dispute exists, then a trial is set within 6 days. If a judgment of eviction results, the Sheriff’s Office can proceed to remove the tenants and their belongings 24 hours later. (Hennepin County, 2019).

Evictions and Emergency Assistance Processes

Challenges include staffing resources and the current complexity of the entire system and how EA fits into it—few can see the system from a point of view big enough to cut through that complexity. Another challenge is the intense focus on incremental change to the EA program, when we would like to look broader to create a system that works for those seeking assistance.

The Hennepin County Human Services Department intends to engage partners from the Family Homeless Prevention and Assistance Program (FHPAP) under the Minnesota Housing Finance Agency (MHFA), along with EA staff, for policy analysis. Once they have made some progress, they would also like to similarly include any other privately funded partners who are interested and willing to be included in the policy pieces. Their view is that with a comprehensive view of the programs and policies, those working to reduce evictions can see more clearly where gaps exist that can ultimately inform legislative priorities, county policy prescriptions, nonprofit work, and more.

Moreover, Hennepin County Human Services is exploring the idea of having staff at Housing Court, but the agency wants to take a holistic view first as “that seems like a reactive point in the game (but it may fit into the design of the larger system)” (Juxtaposition Arts, 2018). Nonetheless, this policy idea aligns with research findings and policy recommendations made by Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid stating the success of tenants in overturning eviction action decisions if they have legal representation. Having county staff available would also provide a reputable source of information for tenants in Housing Court, as many study participants stated that they were not aware that eviction actions remain on their record even in cases where they prevail.

Community Voice and Response

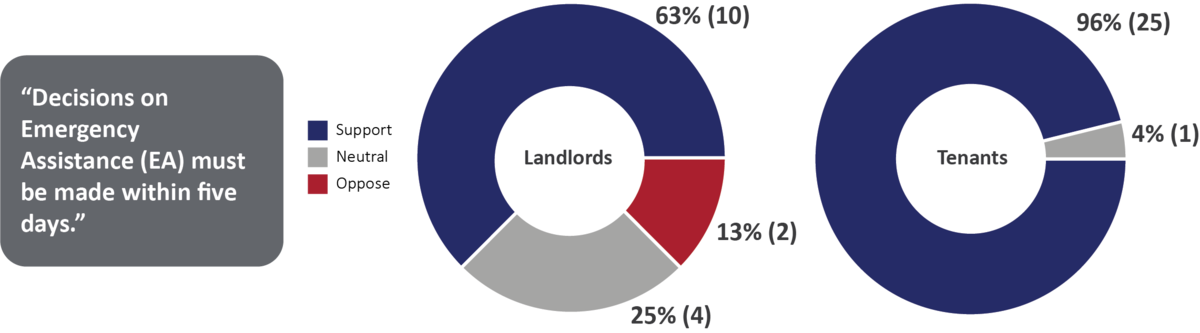

As noted in the larger report, two main themes emerged from tenant interviews regarding the Hennepin County EA/EGA processes. First, both landlords and tenants reported that the length of time it takes to get a decision regarding support from EA or EGA often does not match up with the rapid nature of eviction actions. Second, a number of tenants described the process of applying for EA/EGA as dehumanizing, as if those with whom they were working were giving them money directly from their own pockets. Tenants and landlords alike were overwhelmingly in support of faster deadlines for EA/EGA decisions (within 5 days):

In addition to increasing the speed at which EA/EGA decisions are made, Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid, along with HOMELine and several other community partners, has called for EA/EGA to redefine “emergency” in the statute, streamline the application process, and decrease the length of appeal decisions in an effort to make the process more accessible and human-centered for those in need.

Finally, Dr. Lewis is working as a partner with Hennepin County to re-envision a process of EA/EGA assistance that centers those most affected by evictions. She has shared data and stories from The Illusion of Choice project, which has in turn informed a new partnership between the Pohlad Family Foundation and Hennepin County to implement a “Housing Stability Resource Redesign.”

Policy Recommendation #3: Centering People’s Agency: Ending Current Self-Pay Procedures in Hennepin County Shelters

You know the other irony with this whole system is that, I don't know what it's called but there's a shelter situation where...yes you can come in. Yes you have lodging, you have a bed, you share common space, you get three squares a day. But whatever your money is, you have to give it all to us for $75 dollars, each month, and you're familiar with it. So then how do you get ahead? I mean how do you then say, "Well you know, I don't want to be here forever." You know what I mean? And I learned that as a result of the situation, too. I said "Wow." And then they wonder why folks become dependent and are there forever. (Black female, 70 years old)

To go to the shelter. That was the only way they would help us. If you're in the shelter and let them take a little bit of money from you, or take money from you, and then in that situation, of course. With your own money we'll help you pay for stuff that you coulda paid for if you woulda just gave us that money originally. They were paying two, three thousand dollars a month for the shelter, but was taking more money than that from me. If they woulda just let us save that money for one month, we woulda been outta there the first month. (Black male, 28 years old)

We recommend ending the county’s policy on self-pay at shelters to enable shelters to develop and implement asset-building and financial education programs for shelter guests. The relevant county policies require shelter guests to exhaust all available resources to address their emergency. However, many tenants interviewed discussed the paradox of being evicted because they did not have enough money to pay rent only to enter into a shelter system that required them to pay per bed. Ending self-pay will allow shelters to play a positive and empowering role for distressed shelter guests.

During interviews, several tenants revealed that they often slept in their cars as an act of resistance instead of paying the approximately $30 per bed price to stay at a county shelter. While guests believed that this was a shelter policy, it is actually a Hennepin County policy known as “self-pay,” and shelters contracting with the county are obligated to enforce it. One tenant interviewed illustrated the frustration in paying a shelter for services at a time of hardship when the shelter could be supporting their financial independence: “They were paying two, three thousand dollars a month for the shelter, but was taking more money than that from me. If they woulda just let us save that money for one month, we woulda been outta there the first month.”

Under the self-pay policy, guests of county shelters must exhaust all “available resources” to resolve the emergency for which they are seeking EA/EGA before the county expends reimbursements to the shelter. This Hennepin County policy applies to all county shelters but is not explicitly written into the individual contracts with shelters. The county benefits economically from this relationship because the county shelters (e.g., People Serving People) cannot precisely anticipate the number of guests they will have, which ultimately affects their reimbursement amount.

Relevant County Policies Informing Self-Pay:

- 2.6: All resources available to the family unit must be used to resolve the emergency.

- 2.6.1: Resources are defined as all real and personal property owned in whole or in part and all income, minus basic needs, received from date of application for Emergency Assistance through the disposition date of application.

- 2.6.2: Basic needs are defined as the minimum personal requirements of subsistence restricted to shelter, utilities, food, and other items the loss of or lack of is determined by Hennepin County to pose a direct, immediate threat to the physical health or safety of a member of the family unit.

The Evictions team and the county shelters hope to reimagine this process to serve residents more holistically. Suggestions and critiques made by tenants interviewed and Advisory Council members include:

- Helping guests save money by starting financial help programs as a component of time spent at a county shelter.

- The acknowledgment that the policy to expend all available resources does not help the family out of homelessness; rather, it can compound crisis-based decision making for those affected, limiting their options there on.

- The “rose-colored glasses” view of county shelter turnover rates. At the moment, the average county shelter stay is 32 days (Hennepin County, 2019). However, since many housing insecure tenants refuse to stay in shelters if the staff make them pay for their bed, this form of resentful resistance could negatively skew the average shelter stay; that is, because many people decide not to stay at the shelter, the average shelter stay may not be a reliable indicator of the state of homelessness and housing insecurity in Minneapolis.

Ending the self-pay requirement to enable shelters to implement asset-building and empowerment programs for guests is crucial to housing stability. Many families experience self-pay as a source of frustration and a barrier to exiting homelessness. Ending self-pay, financing shelters up front, and incorporating housing services and financial education into shelter stays are practices the county can promote to empower tenants with resilience-building methods during what is already a distressing time. In this way, the county can play an active and positive role in ensuring housing stability for all. This finding has already spurred a partnership between Dr. Lewis and her research team at CURA and People Serving People. The partnership aims to develop a pilot program that will explore an alternative to self-pay, with the goal of allowing families to retain and grow their financial resources on their way to housing stability, increasing family agency and helping to build family, personal, and financial power.